By Justin Chiu

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n°131

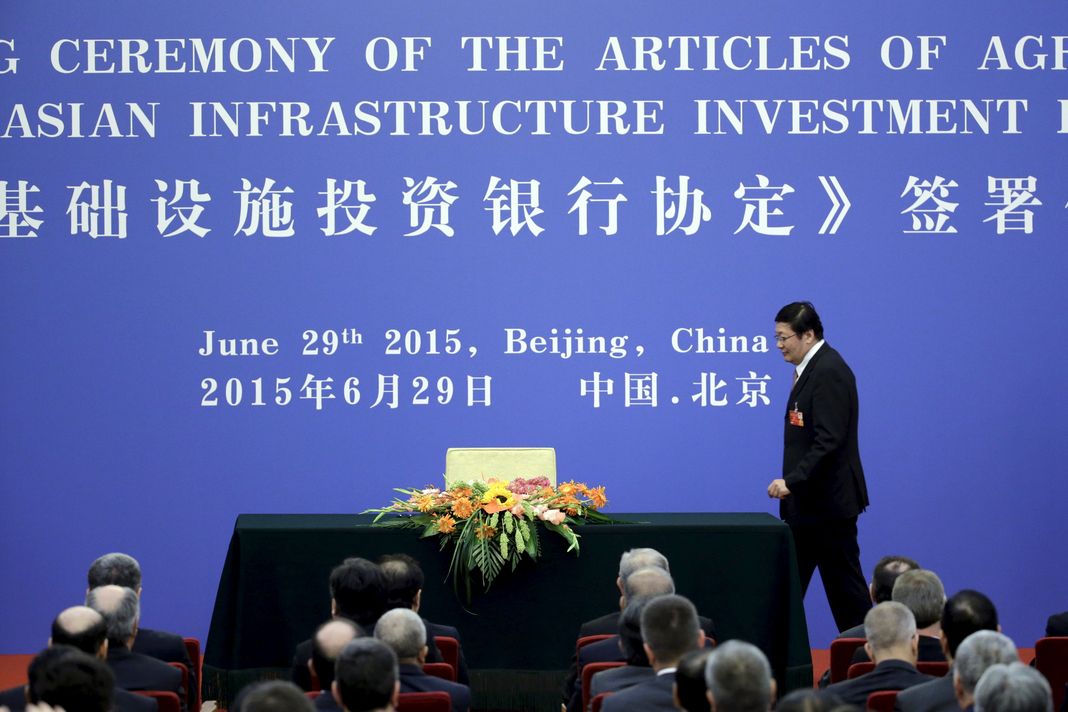

Source: Jason Lee / Reuters pour Le Monde

Source: Jason Lee / Reuters pour Le Monde

On June 29, 2015, the signing ceremony of the statutes of the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) was held in Beijing. Bringing together 57 countries worldwide, this new multilateral bank has established a $100 billion fund of which 30% comes from China. Considered a diplomatic success of the Chinese state, the creation of the AIIB marks a turning point in global finance.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

In September 2013, six months after taking power, Chinese President Xi Jinping presented his overall economy and trade strategy, which bore the title The Eurasian Land Bridge (also called the New Silk Road). In order to secure access to raw materials and streamline the exportation of goods, priority is now placed on strengthening transport networks – both land and sea – and communication between Beijing and its partners in Asia and Europe. However, according to the ADB (Asian Development Bank), a yearly sum of $800 billion would be required to support infrastructure construction in Asia. But the World Bank and the ADB can finance only 20 billion dollars. The draft unveiled by AIIB in October 2013, is indeed a political maneuver. It comes primarily as a response to economic necessity.

Since its accession to the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 2001, China has multiplied its exchanges and especially its trade surplus (382.46 billion US dollars in 2014). In March 2015, Beijing’s foreign reserves accumulated and amounted to 3.730 billion. The first bearer of US government debt with 1.277 billion dollars in Treasury bills (July 2013), today China also invests in the European debt through the ESM (European Stability Mechanism). Nevertheless, to diversify and strengthen the partnership with the South, China has created several transnational organizations, such as the China-Africa Development Fund (2006). This desire to export more capital than manufactured goods, is also expressed by the ongoing establishment of the AIIB in Beijing and that of BRICS Development Bank in Shanghai. Moreover, the role of Eximbank and CDB (China Development Bank) were reinforced by bilateral projects. In this regard, Beijing lent $73 billion to its partners in Latin America for the period 2005-2011, while the World Bank lent 53 million.

Theoretical framework

1. The Transnational Offensive of a Competition State. According to Philip Cerny, the competition State has gradually replaced the welfare State to meet the requirements of global competition. Indeed, in the policy process, the State is now forced to find harmony between domestic requirements and international goals. By the transnationalisation of their activities, networks and strategies, State actors could benefit more from globalization and safeguard the interests of private groups. Thus, contrary to the view of the retreat of the State put forth by Susan Strange, Cerny notes that in some economic-financial areas, State power sometimes multiplies its interventions.

2. The financialization of relationships of domination. In Philosophy of Money, Simmel demonstrates the key role of the monetary economy in the densification of trade. In fact, with money, abstract action among individuals and social groups becomes measurable and concrete. Monetized exchanges therefore reinforce interdependence and domination. In this regard, the capital holder has the power to impose conditions and to assign him or herself privileges. Thus, money becomes synonymous with power.

Analysis

Rich in natural and mineral resources, China nevertheless remains the first importer in the world of these very elements. In order to secure its supply of oil, it is involved in infrastructure construction in Africa (Angola, Nigeria, Sudan and South Sudan), Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), but also more recently in Pakistan, with a large, $46 billion investment program. Regarding the development of energy industries and transport networks, AIIB is to consolidate the efforts already made by the government in Beijing.

Curiously, Chinese firms will be the primary beneficiaries of the AIIB’s investments. In fact, the oil companies – CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Corporation) and Sinopec (China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation) – the largest construction companies – CSCEC (China State Construction Engineering Corp) – and Huawei telecom equipment manufacturers and ZTE jointly gained experience in this kind of complex work linking energy and transport networks. Supported by major Chinese banks, they are able to respond to tenders with very competitive rates. They are counting on additional long-term benefits. In addition, as a shareholder that holds 30% of the company and 26% of voting rights, Beijing could enforce its decisions in this new financial mechanism. In other words, by the export of capital, the Chinese state seeks to support the internationalization of its companies.

Despite pressure from Washington, its western allies and Tokyo’s distrust, Beijing has managed a diplomatic feat. In fact, after an application for membership by the United Kingdom filed in March 2015, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and twelve other European countries have also submitted their requests. Regional actors, Brazil, Egypt and South Africa are also founding members of the new bank. Although the participation of non-Asian countries is limited to 25% of the capital, the essential thing for these States is to not be excluded. All the more as the economic benefits seems significant. Also, to define the governance of the AIIB and assess the viability of projects, China does not need financial expertise from outside.

Anticipating the growth momentum in Asia, establishing the AIIB produced a multiplier effect. ADB – to which Japan is the largest contributor – promised to increase its own funds, which will allegedly rise from 18 to 53 billion dollars in 2017. The scale of the work could be measured by capital flows. Finally, with the creation of this multilateral bank, the Chinese government intends to open untapped markets and to highlight its indisputable leadership in Asia.

References

Cabestan Jean-Pierre, La Politique internationale de la Chine, Paris, Presses de Science Po, 2010.

Cerny Philip G., Rethinking World Politics: A Theory of Transnational Pluralism, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Meyer Claude, La Chine, banquier du monde, Paris, Fayard, 2014.

Meyer Claude, « Le succès éclatant, mais ambigu, de la Banque asiatique d’investissement pour les infrastructures », Le Monde, 1 July 2015, available at :

http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2015/07/01/le-succes-eclatant-mais-ambigu-de-la-banque-asiatique-d-investissement-pour-les-infrastructures_4665869_3232.html

Simmel Georg, Philosophie de l’argent, [1900], trad., Paris, PUF, 2009.

Official website of the AIIB: http://www.aiibank.org/