Oct 20, 2015 | English, European Union, Human rights, International migrations, Passage au crible (English)

By Catherine Wihtol de Wenden

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 132

Source: Pixabay

Source: Pixabay

In 2014, the EU received 625,000 asylum seekers, a figure not seen until then. Previously, the yearly number remained around 200,00 applications. In 2015, 300,000 people from around Europe (Libya, Syria, Iraq, the Horn of Africa) were forced to migrate due to the chaos facing their countries. Besides these facts, the drowning deaths of two thousand people at the borders of Europe are also deplored. Yet, the data continues to worsen. Between 2000 and 2015, an estimated 30,000 people perished in the Mediterranean. The overall number since 1990 stands at 40,000. At the same time, Angela Merkel’s speech in September 2015 was an unprecedented turning point. The German Chancellor announced that Germany was ready to host 800,000 asylum seekers in the coming months. For their part, French President François Hollande and the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Junker, are calling for the creation of a permanent and compulsory system of reception of asylum applications in all European Union member states according to each country’s population and resources.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

The European asylum policy based on the 1951 Geneva Convention defines a refugee as a person fleeing persecution or experiencing legitimate fears. This condition being met, he or she may then apply for a home in a host country. The right to asylum is a universal right that only fifty countries have not yet accepted. But given the diversity of responses of European powers, the EU is continuing to seek to harmony on this topic.

The first instruments of harmonization were used during the first asylum crisis in Europe after the fall of the Iron Curtain. At the time, 500,000 asylum applicants were sent to the European Union (including 432,000 in Germany in 1992). At that time, there was a struggle against “asylum shopping” where applicants made requests to various members of the Union pending on the response from the highest bidder. From now on – and this was at stake during the 1990 Dublin agreements – one single application is acceptable for treatment and response from all EU states. The same goes for the acceptance or refusal of granting refugee status. Since applications were addressed to Germany and Austria during this period, they have requested a sharing of the “burden”. This finally resulted in the Dublin II agreement in 2003. Itself based on the “one stop, one shop” principle. In this case, this means those concerned must now seek asylum in the first European country where they arrive. However, this logic has led to a backlog of applications on state territories located along the external borders of Europe, such as Italy and Greece, poorly equipped to cope with the influx of refugees. In addition, these states have a lesser culture of asylum, unlike Germany or Sweden. Newcomers have sought to leave, firstly avoiding the stamping of their passport. Doing so has kept them from being inevitably sent back to their first country of arrival. Such regulation has brought many locations to a point of saturation; including Athens or Calais and Sangatte in France. Applicants awaiting asylum in the United Kingdom are camping out in these two French cities.

In 2008, the European Pact on Immigration and Asylum (which is not a treaty) stated, among its five principles, the harmonization of European asylum law. It is in this spirit that an office in Malta was created, to harmonize the answers based on applicants’ profiles. A list of safe countries as well as other areas of safety under the control of non-state organizations, and a notification of clearly unfounded applications has therefore passed between members of the Union. This is a state of affairs that has come to restrict all chances for obtaining refugee status. But the Arab revolutions of 2011, the Syrian, Libyan and Iraqi crises combined with the arrival of many Afghans, eventually rendered the Dublin II regulation meaningless. A new, more tolerant practice then allowed the circulation of asylum seekers towards territories where they wanted to go. It also offered more flexibility in determining the processing and application country, depending on the applicant’s choice and its links with a particular European region. This turnaround recently mentioned by Angela Merkel will without a doubt lead to the disappearance of the Dublin II regulation.

Therefore, we note that 2014 and 2015 saw an exceptional influx of asylum requests. Faced with this challenge, the quota proposal made by the European Commission, which was initially snubbed in June 2015, was then followed by a compulsory system. It has now led to a new line between two groups of Europeans. On the one hand, those who accept to welcome refugees, and on the other hand, those who refuse the imposition of such measures such as the Central and Eastern European States, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Denmark.

Theoretical framework

1. Asylum confronted with the influx of Syrians. Should the Geneva Convention still be respected terms of assessing the individual character of an asylum seeker’s profile and the persecution that he or she has gone through or that she or he is fleeing? Should we not make a collective response adapted to this group of people of whom six million have fled their homes since 2011 and four million are abroad today? Some countries have already agreed to host millions of Syrians. They primarily include Turkey: 1.8 million; Lebanon: 1,200,000; and Jordan: 600,00. In other words, the urgency of this crisis does not require an exceptional response to an exceptional situation, as was the case in the past for the Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian boat people, between 1975-1980? There is also the question pertaining to the sovereignty of European countries. Many are having trouble accepting that asylum seekers are imposed on them. Mechanisms such as temporary protection, based on the European directive of 2001, could be applied, as in the past for citizens of the former Yugoslavia. However, these provisions are not part of the proposed solutions.

2. The harmonization of asylum in the European Union. In this political community, each country sets up its own diplomacy. Each has a special relationship with a particular country of origin and whether it maintains its tradition of asylum, given the low visibility of the Union’s common policy. Yet, asylum seekers often have a clear idea of the country where they want to go, for reasons of language, family ties, employment opportunities and benefits. Therefore, the idea that member states would all be seen as similar to them remains purely a pipe dream. In this context, the public opinion on the extreme right has long held that the practice of responding to European countries by affirming their policies here and there without restrictive nuances, exploits this issue which is in the service of migration security policies.

Analysis

The asylum crisis that Europe is currently facing shows that deterrence has reached its limits. Although over the past 25 years it has been the strategy of choice and has seen the continual sophistication of its instruments, this strategy has not reduced regular and irregular entries or lessened the number of requests for asylum. Rather, it emphasizes the existing lines that are currently dividing Europe, between countries in the East and those in the West. Thus, this situation reveals the hostility of the new EU members from the communist bloc. It also renews the disparities between the North and the South. These differences are illustrated by the lack of solidarity between northern European countries – little affected by the arrivals in southern Europe – and states like Italy and Greece. So far, the latter have welcomed the bulk of those arriving. This we saw in Italy with Operation Mare Nostrum, implemented between November 2013 and November 2014. Ultimately, withdrawal wins out on account of EU solidarity principles. However it must be understood in this connection that Europe places its values on this human rights issue and on the shared responsibilities in the decision to welcome – or not to welcome – refugees.

References

Höpfner Florian, L’Évolution de la notion de réfugié, Paris, Pédone, 2014.

Vaudano Maxime, « Comprendre la crise des migrants en Europe en cartes, graphiques et vidéos », LeMonde.fr, [En ligne], 4 sept. 2015, disponible à l’adresse suivante : http://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2015/09/04/comprendre-la-crise-des-migrants-en-europe-en-cartes-graphiques-et-videos_4745981_4355770.html. Dernière consultation : le 17 sept. 2015.

Wihtol de Wenden Catherine, La Question migratoire au XXIe siècle. Migrants, réfugiés et relations internationales, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013.

Oct 13, 2015 | China, Diplomacy, English, International commerce, International Finance, Multilaterism, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English)

By Justin Chiu

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n°131

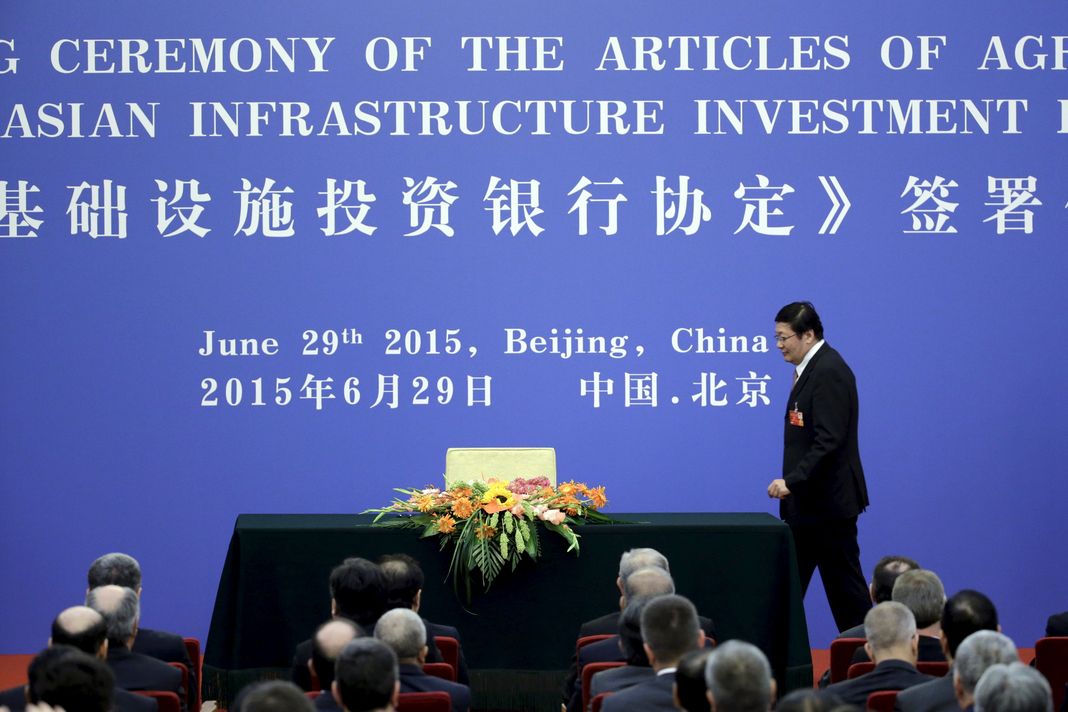

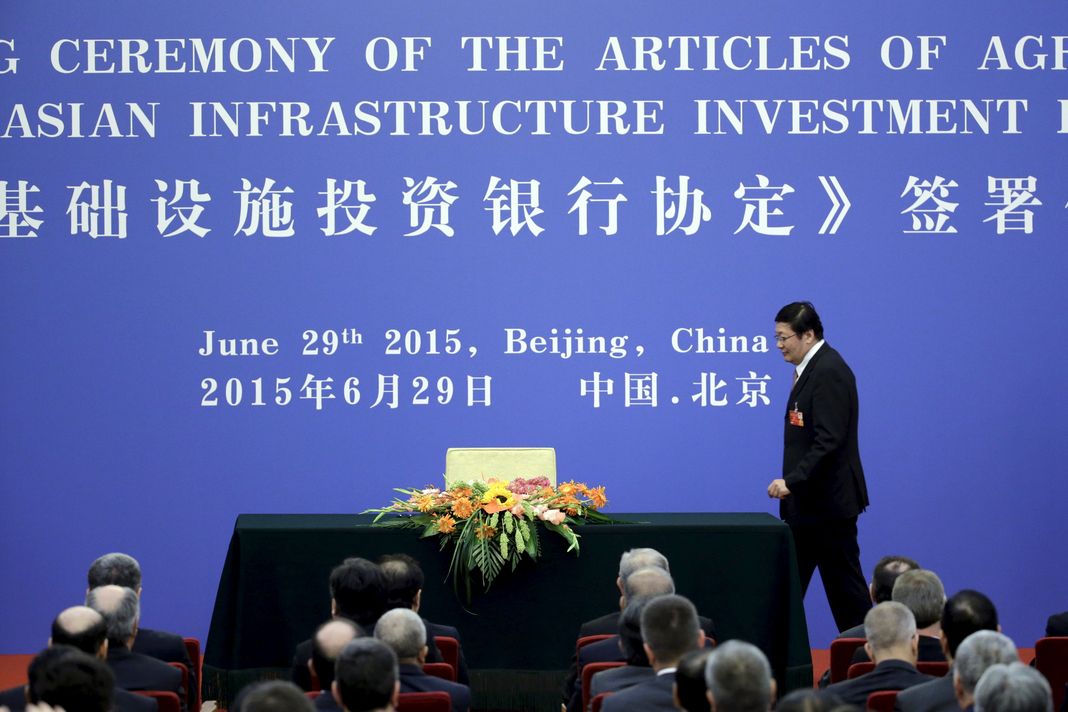

Source: Jason Lee / Reuters pour Le Monde

Source: Jason Lee / Reuters pour Le Monde

On June 29, 2015, the signing ceremony of the statutes of the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) was held in Beijing. Bringing together 57 countries worldwide, this new multilateral bank has established a $100 billion fund of which 30% comes from China. Considered a diplomatic success of the Chinese state, the creation of the AIIB marks a turning point in global finance.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

In September 2013, six months after taking power, Chinese President Xi Jinping presented his overall economy and trade strategy, which bore the title The Eurasian Land Bridge (also called the New Silk Road). In order to secure access to raw materials and streamline the exportation of goods, priority is now placed on strengthening transport networks – both land and sea – and communication between Beijing and its partners in Asia and Europe. However, according to the ADB (Asian Development Bank), a yearly sum of $800 billion would be required to support infrastructure construction in Asia. But the World Bank and the ADB can finance only 20 billion dollars. The draft unveiled by AIIB in October 2013, is indeed a political maneuver. It comes primarily as a response to economic necessity.

Since its accession to the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 2001, China has multiplied its exchanges and especially its trade surplus (382.46 billion US dollars in 2014). In March 2015, Beijing’s foreign reserves accumulated and amounted to 3.730 billion. The first bearer of US government debt with 1.277 billion dollars in Treasury bills (July 2013), today China also invests in the European debt through the ESM (European Stability Mechanism). Nevertheless, to diversify and strengthen the partnership with the South, China has created several transnational organizations, such as the China-Africa Development Fund (2006). This desire to export more capital than manufactured goods, is also expressed by the ongoing establishment of the AIIB in Beijing and that of BRICS Development Bank in Shanghai. Moreover, the role of Eximbank and CDB (China Development Bank) were reinforced by bilateral projects. In this regard, Beijing lent $73 billion to its partners in Latin America for the period 2005-2011, while the World Bank lent 53 million.

Theoretical framework

1. The Transnational Offensive of a Competition State. According to Philip Cerny, the competition State has gradually replaced the welfare State to meet the requirements of global competition. Indeed, in the policy process, the State is now forced to find harmony between domestic requirements and international goals. By the transnationalisation of their activities, networks and strategies, State actors could benefit more from globalization and safeguard the interests of private groups. Thus, contrary to the view of the retreat of the State put forth by Susan Strange, Cerny notes that in some economic-financial areas, State power sometimes multiplies its interventions.

2. The financialization of relationships of domination. In Philosophy of Money, Simmel demonstrates the key role of the monetary economy in the densification of trade. In fact, with money, abstract action among individuals and social groups becomes measurable and concrete. Monetized exchanges therefore reinforce interdependence and domination. In this regard, the capital holder has the power to impose conditions and to assign him or herself privileges. Thus, money becomes synonymous with power.

Analysis

Rich in natural and mineral resources, China nevertheless remains the first importer in the world of these very elements. In order to secure its supply of oil, it is involved in infrastructure construction in Africa (Angola, Nigeria, Sudan and South Sudan), Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), but also more recently in Pakistan, with a large, $46 billion investment program. Regarding the development of energy industries and transport networks, AIIB is to consolidate the efforts already made by the government in Beijing.

Curiously, Chinese firms will be the primary beneficiaries of the AIIB’s investments. In fact, the oil companies – CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Corporation) and Sinopec (China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation) – the largest construction companies – CSCEC (China State Construction Engineering Corp) – and Huawei telecom equipment manufacturers and ZTE jointly gained experience in this kind of complex work linking energy and transport networks. Supported by major Chinese banks, they are able to respond to tenders with very competitive rates. They are counting on additional long-term benefits. In addition, as a shareholder that holds 30% of the company and 26% of voting rights, Beijing could enforce its decisions in this new financial mechanism. In other words, by the export of capital, the Chinese state seeks to support the internationalization of its companies.

Despite pressure from Washington, its western allies and Tokyo’s distrust, Beijing has managed a diplomatic feat. In fact, after an application for membership by the United Kingdom filed in March 2015, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and twelve other European countries have also submitted their requests. Regional actors, Brazil, Egypt and South Africa are also founding members of the new bank. Although the participation of non-Asian countries is limited to 25% of the capital, the essential thing for these States is to not be excluded. All the more as the economic benefits seems significant. Also, to define the governance of the AIIB and assess the viability of projects, China does not need financial expertise from outside.

Anticipating the growth momentum in Asia, establishing the AIIB produced a multiplier effect. ADB – to which Japan is the largest contributor – promised to increase its own funds, which will allegedly rise from 18 to 53 billion dollars in 2017. The scale of the work could be measured by capital flows. Finally, with the creation of this multilateral bank, the Chinese government intends to open untapped markets and to highlight its indisputable leadership in Asia.

References

Cabestan Jean-Pierre, La Politique internationale de la Chine, Paris, Presses de Science Po, 2010.

Cerny Philip G., Rethinking World Politics: A Theory of Transnational Pluralism, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Meyer Claude, La Chine, banquier du monde, Paris, Fayard, 2014.

Meyer Claude, « Le succès éclatant, mais ambigu, de la Banque asiatique d’investissement pour les infrastructures », Le Monde, 1 July 2015, available at :

http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2015/07/01/le-succes-eclatant-mais-ambigu-de-la-banque-asiatique-d-investissement-pour-les-infrastructures_4665869_3232.html

Simmel Georg, Philosophie de l’argent, [1900], trad., Paris, PUF, 2009.

Official website of the AIIB: http://www.aiibank.org/

Jul 27, 2015 | environment, Foreign policy, Global Public Goods, Globalization, Multilaterism, Théorie En Marche

A few months before the COP21, the book by S. Aykut and A. Dahan offers readers valuable insights into the issues related to climate change negotiations.

In clear yet dense language, this manual retraces each and every steps of the construction of the climate regime, since the first warning signs until the Copenhagen Summit. The reader will discover the leading role played by the United States, both in the scientific field and concerning the formulation of policy linked to the problem. The meticulous explanation of the struggles to provide an appropriate framework will particularly allow for understanding of the persistence of numerous disagreements.

In light of the obvious failure of attempts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the authors question the reasons for such inefficiency. Indeed, it results from the gap that has been progressively growing between a “process of governance by the UN [ …] and furthermore, a reality punctuated by the bitter struggle for access to resources [..] and fossil energy”.

Aykut Stefan A., Dahan Amy, Gouverner le climat ? Vingt ans de négociations internationales, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2014, 749 pages including an 83-page bibliography, a list of acronyms as well as an index of graphs and tables.

Jul 26, 2015 | Climate change, English, environment, Globalization, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English)

By Weiting Chao

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 130

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia

Six months before the Climate Conference (COP21), the 26th World Gas Conference (WGC2015) was held June 1-5, 2015, in Paris. Organized by the IGU (International Gas Union), the event brought together more than 4,000 representatives from 83 countries from the biggest global industry players including BP, Total, Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, ENI, BG Group, Statoil, Qatargass, PetroChina, etc. Climate change, which now takes center stage, incited these actors to discuss themes linked to energy transition.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Negotiations between states concerning global warming began at the end of the 1980s. During the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, 153 countries signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In 1997, signatory countries adopted the Kyoto Protocol, which still to this day, continues to be the only binding agreement for developed countries to reduce their GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions between 2008 and 2012. From the moment the protocol came into force 2005, the post-Kyoto period was evoked. However, the signature of the new treaty is still proving to be difficult, as even after the failure of Copenhagen (COP15), in 2009, no significant progress towards a universal treaty has been observed. As a result, in 2012 in Doha, the Kyoto Protocol was extended until 2020. As for the adoption of a new treaty, it was postponed until COP21, which will take place in Paris in December 2015.

A few months before the event, WGCPARIS2015, the most important global gathering of the oil and gas industry, also took place in Paris. Discussions included the market value of the gas chain, exploration and production, international transmission, energy innovation, etc. During the summit, the companies underlined the crucial role of natural gas, which according to them produces two times less CO2 than coal. As such, it could help decrease GHG emissions. Moreover, on June 2 of this year, six European oil company executives (Shell, ENI, BP, BG group, Total and Statoil) wrote an open letter in Le Monde to encourage all state actors to collectively fix carbon price in order to promote energy efficiency. They also requested that the UNFCCC executive secretary assist them in holding a direct dialogue with the UN and Party countries within the context of COP21.

Theoretical framework

1. A Triangular diplomacy. Since the advent of a globalized market and the accelerated pace of technological change, states no longer control but a small part of the production process and direct less and less trade. However, today large energy groups hold a decisive position and act as political authorities, sometimes to the point of competing with governments. This transfer of power in favor of economic operators has led to the emergence of a few diplomacy based on the entanglement of three types of interactions: state to state diplomatic relations, state to firm and firm to firm. Indeed, in many situations, the negotiations that they hold amongst themselves often seem more important. Thus, the results of their negotiations strongly influence the direction of public policy.

2. The paradox of offensive protectionism. In a free market context, large companies maintain interventionist policies aiming to monopolize their portion of the market. Thus, they agree amongst themselves to limit their production, fix prices, agree on their respective market share and promote political, technical, economic and industrial progress. In short, they aim to create an international cartel. Therefore, these majors forge institutional arrangements, and then determine a source of international authority. Free and open competition, is therefore hampered; potential buyers have no other option than to accept the situation, in other words, to submit to it.

Analysis

Concerning energy, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases produces around 35% of emissions, of which more than 56% come from oil and gaz. According to the IEA (International Energy Agency), efforts in this sector to reduce greenhouse gas remain essential. On the one hand, states require the cooperation of firms. On the other hand, as operating costs and benefits in this area appear to be significantly affected by new regulations, many of these operators are seeking to directly influence government decisions. As such, during the first negotiations, which were held in the 1990s, the vast majority of western petrochemical industries declined to adopt the reduction of CO2 emissions imposed by governments and furthermore, opposed any timetable related to their reduction. Organized primarily by the GCC (Global Climate Coalition), they managed to significantly slowing the process by obtaining agreements when negotiating the UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol. With government power, ostensibly eroded, entrepreneurial pressures were a considerable obstacle to climate policy. However, at the end of the decade, industry support for the GCC has gradually faded. Several of its key members, such as BP and Shell, for example, have left the organization. Finally, in 2002, after thirteen years of operation, the GCC was officially dissolved. The virtual disappearance of anti-climate groups reflects a general trend of firms that become increasingly cooperative. Indeed, organized associations, into cartels, direct these significant changes arising from technological innovations and economic benefits either overtly or covertly. Thus, the IGU, founded in 1931, has more than 140 members representing 95% of the global gas market. It includes OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) companies, western super-majors as well as new oil giants in emerging countries such as PetroChina. Every three years, these companies gather at the World Gas Conference in order to establish a common strategy. The key criteria are decided in negotiations where the big oil companies play a predominant role. Fundamentally, these standards have fostered the development of new types of businesses for which potentially high profits – such as renewable energy, manufacturing innovations, new modes of transportation and intellectual property are projected.

This year, companies have forcefully shown how natural gas, which they claim to be the cleanest of fossil fuels, would form the principal vehicle for a good energy transition. The increased use of this resource could bring substantial capital into an emerging sector still fragmented and disorganized. Note that more than $670 billion was spent in 2013 to explore new reserves of fossil fuels. Moreover, the acquisition of BG Group by Shell, the amount of the transaction amounted to 47 billion pounds (64 billion euros), is an exceptional deal. With this merger, Shell – already very active in the field of gas – will increase production by 20% and its hydrocarbon reserves by 25%; besides that this super-major is already spending billions for exploration of the Arctic and projects related to the oil sands of Canada. Now, according to a recent analysis published by the journal Nature, the latter two projects are incompatible with the prevention of climate change, considered hazardous. Moreover, with the energy transition, a considerable amount was paid in order to invest in infrastructure such as the construction of the gas pipeline. In the United States, from 2008 to 2012, the amount of electricity generated from natural gas increased by over 50%. If current trends continue, this energy should account for nearly two-thirds of US electricity by 2050, consequently causing a massive renewal of equipment.

As for the introduction of a carbon pricing system that applies to all countries, firms gather around a common interest, namely the proper functioning of market mechanisms and the development of related regulations. Several companies actually use an internal carbon price to calculate the value of future projects and guide decisions on investment. In these circumstances, the price of carbon, which certain companies have already fixed, assumes, if it became the market price – a much stronger impact than the policies pursued today by governments.

Spokespeople for the gas industry, the major energy sector companies have presented their objectives not only to states but also to the concerned populations. Moreover, they have set out the role that they intend to play during the COP21 that will soon take place in Paris. However, it appears that the technology and resources they intend to use and in which they wish to invest exclusively respond to a techno-financial logic largely incompatible with a significant environmental protection policy. In effect, their offensive protectionism, which resulted in the establishment of a cartel in the energy sector, could lead to energy transition whose contents would be designed expressly for their advantage. This cartel may soon be agreed upon by states in an upcoming agreement.

References

Stopford John, Strange Susan, Henley John, Rival States, Rival Firms. Competition for World Market Shares, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Strange Susan, The Retreat of the State. The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Vormedal Irja, « The Influence of Business and Industry NGOs in the Negotiation of the Kyoto Mechanisms: the Case of Carbon Capture and Storage in the CDM », Global Environmental Politics, 8 (4), 2008, pp. 36-65.

Jul 20, 2015 | Africa, Defense, English, Passage au crible (English), Security, Terrorism

By Philippe Hugon

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n° 129

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia

On March 23, 2015, Al-Shabaab (“the youth” in Arabic) attacked Garissa University in Kenya, leaving more than 150 dead. These actions, targeting Christian students, were committed in an extremely violent manner in a symbolic place known for dispensing knowledge. They occurred one month after Al-Shabaab pledged its allegiance to Al-Qaida and threatened shopping centers of western origin. Let us recall that in three years, Kenya has seen three murderous attacks including the attack at the Westgate Mall in 2013. Similarly, the Ugandan capital Kampala was attacked in July 2011. As for Ethiopia, it remains under strong threat.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

With its more than 10 million inhabitants spread over 638,000 km2, Somalia has never been a state. Indeed, despite its independence in 1959, it continues to be organized into a system of clans and sub-clans. But this clan society does not appear anarchical as Somalis speak the same language – Somali – and form a homogenous ethnic group marked by its pastoral tradition. The Somali people maintain values of honor, hospitality and revenge. In this country where nearly 100% of the population remain devout followers of Islam, Islamic law coexists with tribal or clan law.

Today, however, we are seeing significant changes. Religion, which until now was a source of unity in Somalia, is bringing traditional Sufi Islam into conflict with Salafist Islam. In addition, a relative social disintegration results from the opposition between the younger and the older generations concerning code of conduct. The rise in power of the Shabaab harkens back to these determinant differences. For the past 35 years, Somalia has undergone a process of clan-based balkanization as well as socio-political chaos that has left more than 500,000 dead. Lead by a warlord, each clan is traditionally armed with a militia. The confrontations are due to disenchanted youth who have only been socialized within a context of violence.

Otherwise, several elements that have been harmful to the country are coming together and are causing further fragility. To that effect let us mention Islamic influences (Muslim Brotherhood, Salafists, the role of Eritrea), the effects of demographic pressure on rare resources or else the generalization of a parallel economy, which makes a host of illegal traffic possible. At the same time, this society finds itself drawn into globalization by dint of its diaspora. Information technology also leads to its global insertion, as does the taxation of NGOs or sea piracy with attacks on sailboats or freighters. Thus, let us recall that the tax on oil tankers (20,000 ships and 1/3 of the world’s tankers pass by the strait) made up 4,000 acts of piracy between 1900 and 2010 as reported by a census. Of course, the Atalante has successfully reduced that number since then, but it has never been able to stop them completely.

Until 1991, Somalia was led by Barré’s socialist and USSR-linked regime. Between 1992 and 1994, military interventions – whether international or American (“Restore Hope”) – all failed. A civil war raged between 1991 and 2005. In the summer of 2006, Islamic Courts, notably supported by Eritrea, then took power against faction leaders through the shura. They brought together a variety of tendencies (Hizbul Islam, “Islamic Party”), al-Islah (similar to the Muslim Brotherhood), extending to the radical Al-Shabaab Islamists, accused of being the African version of Afghanistan’s Taliban.

In place of negotiations with the moderate components of Islamic Courts, the United States and countries in the surrounding region preferred to support a government in exile that was neither representative nor legitimate. At the end of 2006, militarily supported by Ethiopia and the United States, and indirectly by Kenya, Uganda and Yemen, this transitional power regained control of Mogadishu, without controlling the warlords. An African Union Force, the AMISOM (African Union Mission in Somalia) was put in place in 2007. Al-Shabaab then began its terrorist actions, primarily in Mogadishu (end of 2009 against the African Union, suicide attack in October 20011, April 14, 2013).

Composed of an organized movement for the past ten years, Al-Shabaab may now have as many as 5,000 to 10,000 combatants. Some were trained in Afghanistan; others are from Al-Ittiyad, Somali group of Islamic movements formed in the 1980s. Others were recruited and trained by Islamic Courts in power since 2006. Then, they increased their influence when the Islamic Courts fell to the coalition of eastern African countries, supported by the United States. Their multiple demands are based on Somali nationalism and the desire to build an Islamic state founded on sharia law. They also derive their power from the control of traffic carried out by youths without prospects. Al-Shabaab then offers these youths the implementation of a global jihad by dint of their insertion into transnational networks.

Theoretical framework

1. Intergenerational violence. Within Somalia, violence results from conflict between Shabaab members, – youths socialized in violence – and the official government; the fights being essentially lead by the African force AMISOM.

2. Transnational violence. Shabaab violence also carries a regional and transnational dimension which is explained by the presence of numerous Somalis in neighboring countries (more than 600,00 refugees in Kenya), Somalis who are explicitly showing a desire to destabilize the security system of neighboring countries, beginning with Kenya. They are linked to money transfer circuits because Somalia has become a territory of proxy war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, all the while remaining a concern for countries allied with the United States that are fighting against jihadism.

Analysis

The Shabaab can be analyzed as a Somali movement. Stemming historically from Islamic Courts, they are young people whose only prospects are handling arms, violence and trafficking. They can easily be deployed within the Somali because of the government’s low level of legitimacy. Taking into account the incapacity of the State to control its territory and to ensure a minimum of state functions, they combine intimidation by violence and protection of populations. Certainly, they have set up an unpopular system based on charia law – banning the chewing of qat and listening to music -, but they also established a system to facilitate international exchanges. This is why they benefit from support allowing them a certain conventional military capacity.

Their primary resources continue to be the authority that they impose on trafficking and the local taxes that they deduct from businessmen and traders. Finally, they also draw their income from the relations that they maintain with pirates. Supported by forces from Afghanistan and Eritrea, Shabaab forces opposed the federal transitional government. At the end of 2010, they still controlled a large part of Mogadishu as well as the center and the South of the country. However, against AMISOM military action, they ultimately lost the ability to cause harm in the heart of Somalia. They then had to leave major cities, starting with Mogadishu. Following that, they disseminated into rural zones and blended into the general population. In addition to this, on September 1, 2014, they lost their leader Ahmed Abdi Godane, who was replaced by Ahmad Umar.

Their action has become particularly regional and transnational. Indeed, as in the case of Boko Haram, the regionalization of their interventions outweighs their loss of control on Somali territory. Today, it seems to have been proven that they had links with money transferring companies, certain Kenyan NGOs as well as with the diaspora. With the support of refugees or Somali emigrants, they can also progressively fit into Jihadist networks of global proportions. Via suicide attacks or terrorist actions, they are seeking to conduct asymmetric battles that seek media exposure by horror. Of course, they are not currently participating in a global jihad. However, they have created personal and organizational ties with groups affiliated with Al-Qaida or Boko Haram, which clearly indicates their long-term objectives.

Suffice it to say that neighboring countries are now threatened more and more. With over 700 kilometers of shared borders with Somalia, Kenya appears to be quite politically divided. The country is henceforth seeking to grow its military, all the while avoiding tensions between Christians – who represent three-fourths of the population – and Muslims. It is also seeking to reassure tourists and businessmen. As for Jubaland, located in southwestern Somalia on the Kenyan border, it acts as a buffer region and has a largely Somali population. The acts by Al-Shabaab committed on this territory seek to fuel religious tensions and to oppose political forces. As for Ethiopia, it has until now been spared, although it shares 1600 kilometers of its borders with Somalia. Organized into a federal state, its population is composed of a majority of Somalis primarily living in Ogaden. But this country continues to be a pivotal state allowing the United States to wage war by proxy. It is therefore unavoidable that military actions within Somalia be soon transformed into terrorist actions linked to transnational networks and Somali expatriates.

Weighing heavily on tourism and business with the West in Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda, media coverage of horrific events seek to sow terror and to win media wars. In the case of Somalia, as in Afghanistan or with Boko Haram, it appears that military solutions lead by AMISOM can only be of limited efficiency. Indeed, sustaining solutions continue to be political. They pass by the establishment of state structures and a legitimate government.

References

Hugon Philippe, Géopolitique de l’Afrique, 3e ed., Paris, SEDES, 2013.

Mashimongo Abelard Abou-Bakr, Conflits armés africains dans le système international, Paris, L’Harmattan 2013.

Véron Jean-Bernard, « La Somalie cas d’école des Etats dits “faillis” », Politique étrangère, 76 (1), print. 2011, pp. 45-57.

Source: Pixabay

Source: Pixabay