Mar 15, 2016 | English, Human rights, Nobel Peace Prize, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English), Terrorism

By Josepha Laroche

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n° 137

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

The Nobel Committee, reunited in Oslo, awarded this year (on October 9, 2015) the Nobel Peace Prize to the quartet who has been leading the « national dialogue » in Tunisia for more than two years. The committee pays here a tribute to « its decisive contribution in the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia in the wake of the ‘Jasmine Revolution’ of 2011 » This group is formed of four civil organisations: 1) The Tunisian General Labour Union, UGTT. 2) The Employers’ Association, the Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts (Utica). 3) The Tunisian Human Rights League. 4) The Tunisian Order of Lawyers. The jury indeed considered that they collectively took essential steps to de-escalate the conflict between islamists and non-islamists at a time when the country was on the brink of civil war.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

During winter 2010, young unemployed graduate Mohamed Bouazizi, like many other young Tunisians, sells fruits and vegetables on Sidi Bouzid market to survive. Lacking administrative license, Mohamed Bouazizi is arrested and his products confiscated. Not able to defend his case, he chooses to set himself on fire on December 17, 2010. From then, in every town and village, a major part of the Tunisian population expresses its solidarity with the young man. At the same time, protests rise against the regime, held responsible for mass unemployment and corruption undermining the economy. In the following days, the whole country flares up as the government fights the protests through ruthless police crackdowns. Eventually, after a month of riots and a major strike, the regime collapses. In spite of reshuffling the government and some vague statements towards appeasement, President Ben Ali has to escape to Saudi Arabia on January 14th, 2011, putting an end to 23 years of unchallenged reign. This historic phase is soon called the “Jasmine Revolution“.

Mohamed Ghannouchi forms then a transitional government of national unity. Simultaneously, all political prisoners are set free, Human Rights League reinstated and the principle of total freedom of information proclaimed. Finally, the Department of Communication, accused during Ben Ali’s regime to censor the press and impede freedom of speech, is suppressed. Facing the pressure, Ghannouchi has to resign as well on February 27th, 2011. He is replaced by Bourguiba’s former minister, Beji Caïd Essebsi. The state of emergency, in place since January 2011, is extended. After the legislative elections of October 26, 2014, where anti-islamic party Nidaa Tounes (Call of Tunisia) comes in first, the Assembly of People’s Representatives replaces the constituent assembly. In the second round of the presidential election organised on December 21, 2014, Caid Essebsi wins the election with 55,68% of the votes cast, against 44,32% for Marzouki. Caid Essebsi becomes then the first president accessing power through a democratic and transparent election. After several months of political instability, troubles and a period of institutional trial, Tunisia seemed to have gained some of a stability. However, the country was soon severely hit by several islamist operations. Firstly, the attack led by the Islamic State against the Bardo museum on March 18, 2015, results in 24 killed (21 tourists, one policeman and two terrorists), and 45 injured. Then, on June 26th, 2015, Daesh targets the Port El-Kantaoui seaside resort in the so-called Sousse attacks, killing 39 persons and wounding 39 others. Lastly, the terrorist organisation also claimed responsibility for the suicide-bombing that took place in Tunis on November 24, 2015 and hit the presidential guard.

Theoretical framework

1. A Nobel for a secularisation process. Built throughout decades, the Nobel diplomacy is now clearly stated and identifiable. Founded on humanist values stated from 1895 onwards by Alfred Nobel in his will, the organisation is now able to take marked positions in international matters. For instance, in awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to activists in favour of a democratic and secular Tunisia, the Norwegian Committee expressed its support against islamists they are victims of. In fact, the committee intends to bring all its weight in the political struggle actually taking place in the country. Even better, further than Tunisia, the Committee actively takes the side of all of those who fight Daesh throughout the world.

2. A Nobel for an entire civil society. The very strict conditions regarding Nobel awards, detailed by Alfred Nobel himself and enforced in 1901 do not allow the Committees – whether it be Physics, Chemistry, Physiology-Medicine, Literature or Economy – to award the Nobel to more than three laureate for one prize. It must be noted, indeed, that the Oslo Jury sidestepped and even transgressed the ban when nominating the quartet as sole and unique recipient of the prize. However, one must understand that through the quartet, the Nobel institution distinguishes rewards and politically supports the entire Tunisian civil society.

Analysis

We count today several hundreds of thousands of deaths in the war that has been raging for 4 years now in Syria. A war that begun, in fact, in 2011, in the wake of the Arab Spring triggered by the Tunisian Jasmine Revolution. Daesh islamists (Islamic State) leading the fights against both troops of shiite President Assad and Kurds, took over several cities and especially large territories in eastern Syria. So much so, the conflict has been internationalised insofar as Russia and Iran offer military backup to the regime, while an international coalition, led by the United States, endeavour to contain the Islamists’ progression. However, the military achievements run farther than this geographical area. Indeed, Iraq, Kenya, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Somali and Afghanistan – to name only a few weak links – appear to be deeply unstable and destabilised by Islamist movements, whether it be Daesh, the Islamic front, Al-Qaida, Bokoh Haram, AQIM (Al Qaida in Islamic Maghreb) or AIG (Armed Islamic Group).

In such international context, awarding the Nobel to the quartet this year has particular significance. That four Tunisian associations promoting human rights and secularisation received the Nobel must be understood as a clear political engagement towards their mission and objective. With this award, the Nobel institution enshrines their political orientations bestowing on them the worldwide prominence and reputation of the prize, and states once again its diplomatic line built year after year. Yet, the institution has been steadily opposing the Nobel’s philosophy to the States. For this to happen, the institution is not reluctant to – through its global rewarding system – interfere in ongoing disputes, with the clear aim to influence, modify, reverse or oppose prevailing rationales. In many ways, it may be seen as a diplomatic intervention policy. For the record, the Norwegian Committee designated the OPCW as the 2013 laureate (Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons) in charge since 1997 to monitor the compliance with the Prohibitions of Chemical Weapons Convention, signed in 1993. At that time, this organisation was specifically coping with the Syrian case, in the wake of the chemical attack that took place in Damascus, on August 21, 2013. In this case, the Nobel diplomacy intruded in the States High Politics, irrupting in the global arena to interfere with the political handling of the Syrian conflict. Furthermore, as it payed a tribute to collective security and multilateralism, and put these notions on the global agenda, the Nobel institution established itself as an essential intermediary to state parties involved in the war.

The 2015 Nobel awards proceeds from the same diplomatic template. This template may be deciphered as such: 1) identify a conflict, 2) clearly take a side by awarding a Nobel prize to one of the parties, 3) act as a regulator by creating and securing international norms. But awarding a Nobel to the entire Tunisian society clearly follows a new pattern. This previously unseen choice marks indeed a significant milestone for the Nobel institution, stating its symbolic significance and repeated global impact on world’s state powers, in accordance with its very own positions.

References

Benberrah Moustafa, La Tunisie en transition. Les usages numériques d’Ennahdha, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2014. Coll. Chaos International.

Bono Irène, Hibou Béatrice, Meddeb Hamza, L’État d’injustice au Maghreb. Maroc et Tunisie, Paris, Khartala, 2015.

Laroche Josepha, Les Prix Nobel. Sociologie d’une élite transnationale, Montréal, Liber, 2012, 184 p.

Laroche Josepha, « L’interventionnisme symbolique de la diplomatie Nobel», in : Laroche Josepha (Éd.), Passage au crible de la scène mondiale. L’actualité internationale 2013, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2014, pp. 119-123.

M’rad Hatem, Le Dialogue National en Tunisie : Prix Nobel de la Paix 2015, Paris, Editions Nirvana, 2015.

Feb 27, 2016 | China, environment, Globalization, Human safety, International Political Economy, Passage au crible (English)

By Clément Paule

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n° 136

Source: BBC

Source: BBC

On the evening of August 12, 2015, a blast shook off Tianjin City, the fourth most populated urban area of the People’s Republic of China. According to Chinese media, the incident had been caused by accidental fire of a storage station containing ethanol and alcohol based products. It is not the first time the 15-million metropolis, located in North-West China and one hundred kilometers away from capital Beijing, faces that kind of event. Two months earlier, a series of huge explosions destroyed the Binhai port area and adjoining residential zones, resulting in 173 killed and about 700 injured.

The disaster originates from a warehouse, property of the Chinese company Rui Hai Logistics, where large quantities of hazardous chemical products were being stored. In this case, media mentioned that several hundreds of tons of sodium cyanide – used in gold mining exploitation – were stored in the warehouse, exposing the population to major water and air pollution risks. This is why Chinese authorities issued an evacuation order concerning 6000 residents and launched large scale cleaning operations. According to Press agency Xinhua, 17 000 households and 1700 companies overall were affected by these events, while a study carried out by Crédit Suisse assesses the damages to 1.3 billion dollars.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Some elements related to the country’s recent history may set the context. The situation is still marked by ongoing economic slowdown with growth figures increasingly called into question, whilst the government has devaluated the Yuan twice. On a political level, we may highlight the intensification of anti-corruption measures driven by First Secretary Xi Jinping that resulted in the arrest of several CCP leaders (Chinese Communist Party). Some authors, such as sinologist Jean-Pierre Cabestan, outline an increasing militarisation of the regime coping with the downturn of the leading model pushed forward since the 80’. On top of this, a series of major industrial disasters occurred such as the August 2014 explosion of an automotive parts manufacturer in Kunshan (146 victims), or the deadly fire of a slaughterhouse in 2013 in the Jilin Province. In this regard, NGO (Non Governmental Organisation) China Labour Bulletin has recorded more than three hundred similar accidents causing death of several hundreds of workers since late 2014.

In this context, the Tianjin Township has a strategic role given its location as maritime entrance of capital Beijing and as international hub for transportation and logistics. Some 540 million tons of material transit every year, placing Tianjin in the international ports top ten. Close to the central government, the city experienced an unprecedented growth in the last decades, enough to be nicknamed “The New Manhattan”. Indeed, special economic zone Binhai showcases technological innovation in aeronautics, electronics, petrochemicals or pharmaceutics. Estimated to 143 billion dollars in 2014, its GDP (Gross Domestic Product) increased by 15,5%, more than the double of national average. This outstanding economic take-off has given rise to chaotic urbanisation and environmental damages caused by frenzy industrialisation over the last three decades. The disaster of August 12, 2015 strikes at the core of the system and highlights the paradox of frantic modernisation.

Theoretical framework

1.The “black hole” of globalisation. Industrial insecurity brought to light by this incident is due to systematic bypass of economic regulations. Moreover, collusion capitalism or crony capitalism operating at the heart of the Chinese regime creates unregulated zones or black holes (Susan Strange) eventually jeopardising its authority.

2. Selective liability. Facing this complex crisis, the government relies on solutions applied to previous disasters, such as the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Besides controlling information streams, culprits are identified and held responsible for the failure of the whole political and administrative system.

Analysis

Several investigations regarding the catastrophe rapidly revealed a series of infringements to current regulations, in spite of recent strengthening of existing legislation. The devastated warehouse contained 40 times the legal limit of sodium cyanide, stored without any legal operating permits. Moreover, the first residential buildings were only 600 meters away from the site of the explosion, well underneath the legal threshold of 1 km. It is to be noted that Rui Hai Logistics were not operating outside the regulatory framework as they passed successfully several surveys, let alone a consultancy audit. However, the audit report did not mention the immediate vicinity of residential areas as a problem. These series of breaches to security procedures reveal how deep the collusion goes between local town officials and the incriminated company. The company’s stakeholders admitted to using their networks of influence – referred to in China as guanxi – as well as corruption of civil servants, to develop their activities. Such predatory techniques might be the harbinger of pervasive deviating behaviour that township authorities apparently fail to contain, due to lack of political will or resources.

It should be underlined that the emergency response is also faulty, as some sources pointed out the inexperience of temporary employed firemen sent to the front line to extinguish a localised fire. In fact, explosions would have been caused by the contact of water with specific substances such as sodium cyanide, releasing quantities of inflammable gases. Besides, the rushed evacuation of thousands of people and lack of clear communication during the crisis spurred an unusual wave of protests. Several spontaneous demonstration gathered hundreds of residents concerned with water and air contamination from hazardous chemicals. Protestants also claimed for re-housing solutions, but only some of them were granted a compensation agreement. Facing the burgeoning protests, the Chinese state implemented a systematic censorship of the contradictors, in the name of the fight against misinformation and rampant rumours. Dozens of websites were then taken down by the Cyberspace Administration of China. Hundreds of user accounts on the WeChat and Sina Weibo social networks were also blocked. In a press release of august 18, 2015, NGO RSF (Reporters Without Borders) drew attention to this reinforced control leading to sometimes harsh exclusion of foreign journalists. Summoned to publish official dispatches, some of the national media close to the CCP nevertheless criticised the lack of transparency in the behaviour of city officials, potentially fuelling conspiracy theories.

Never formally called into question, the central government launched a series of investigations that led to the arrest of a dozen of individuals, starting with Rui Hai Logistics leaders. Some senior officials were also placed under investigation, such as M.Yang Dongliang, Director of the State Administration for Work Safety. In this regard, one must note that this targeted repression is in line with the anti-corruption measures enforced by Xi Jinping since he first came into power in 2012. For now, this strategy of targeted liability seems to be an attempt to placate public protests. But these empty statements cannot cover the lack of structural reforms and the need to foster a genuine risk management culture. As this disaster is only a temporary halt to entrepreneurial implementation strategy in Tianjin, the scale of the damages opened up the way to Chinese and International insurance companies that have already absorbed a large part of the losses incurred. In a close future, this sector might indirectly be part of a more efficient regulatory environment than the one based on a political system that operates in secrecy and is rotten by conflicts of interests.

Analysis

Cabestan Jean-Pierre, Le Système politique chinois. Vers un nouvel équilibre autoritaire, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2014.

Laroche Josepha, « La mondialisation : lignes de force et objets de recherche », Revue internationale et stratégique, (47), 2002, pp. 118-132.

Site de l’ONG China Labour Bulletin : http://www.clb.org.hk [25 octobre 2015].

Feb 19, 2016 | Digital Industry, English, International Finance, Internet, Passage au crible (English)

By Adrien Cherqui

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n° 135

Source: Flickr

Source: Flickr

The American financial regulation organisation CFTC (US Commodity Futures Trading Commission) has made public on September 17th 2015 that any virtual currency may now be considered as a commodity. This statement aims to secure Bitcoins’ high volatility, and entrusts the CFTC with monitoring powers over this currency highly sought for black markets operations on the Dark Web.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

The Dark Web consists in non-indexed online information, invisible on traditional search engines. It is a main component of the Deep Web and is not be confused with surface web. The Dark Web is only accessible via specific tools such as the anonymous network TOR, and has a wide variety of applications. On the one hand, this significant portion of the Internet could bypass political restrictions over the web and be used as a tool for free expression, but on the other hand, it also hosts illegal activities related to cybercriminality.

Launched in February 2011 by Ross Ulbricht, Silk Road is one of the biggest commercial platforms on the Dark Web. From the beginning, the website has offered illegal products such as drugs, firearms, forged documentation or credit card numbers. Shut down in October 2013 for the first time, the website is definitely suspended in November 2014 during the operation Onymous, jointly led by the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation), Europol, Eurojust and other organisations aiming at a complete stop of more than 410 similar websites.

2015 is a critical year for the cybercriminal ecosystem. On February the 4th, 2015, Ross Ulbricht, who has accumulated a 18-million-dollars personal fortune, is charged with computer hacking, criminal enterprise, money-laundering and drug trafficking, amongst others. Later, Shaun Bridges, federal agent in charge, confesses he himself embezzled $ 820 000 during the investigation. This series of closures is followed by the opening of new commercial platforms on this hidden side of the net. Evolution Market is for instance a major leader of these black markets. Nonetheless, the platform suddenly closes and reveals a major fraud. 12 to 35 million euros stocked as bitcoins are siphoned away by administrators using an exit scam. These bitcoins came from Evolution Market users’ electronic wallets. In the following crisis, the value of the virtual currency drops by 22% compared to the dollar, even though the bitcoins to dollars exchange rate was being published on the New York Stock Exchange since May 2015.

Theoretical framework

1. The digital transformation of criminality. Technological tools are used by criminal networks to elude public authority regulation. Subsequently, nothing is stopping the expansion of international criminality.

2. Regulation by the state. Modern states were built up with strong regulations powers, holding exclusive responsibility over several functions deemed as necessary to exert political domination. Norbert Elias showed that progressive absorption of political and economic activities secured the authority of the administrative system, especially needed to create money.

Analysis

Development and democratisation of the Internet and communication tools spurred globalised changes affecting all kinds of social interactions. Ideas, goods and services are today accessible directly online, and take part in a process of digital transformation, blurring the concepts of borders and temporality. Internet’s ubiquity reshaped social, political and economic issues usually tackled by public authority. The Web, and the Dark Web in particular are perfect tools for skillful individuals (Rosenau), enabling them to bypass surveillance programs and censorship without being tracked or identified.

But the Dark Web showcases as well illegal products and services. More and more fight over a highly competitive market led by Agora, Alphabay and Nucleus. The demise of Silk Road has been followed by the rise of similar black markets, contributing to the complex construction of a criminal ecosystem; a space where every protagonist has innovative strategies to gain new market shares. To this end, black markets spurred professionalisation and specialisation in terms of product (stolen data, malware programs, hardware, drugs, weapons, forged documentation, counterfeit goods, etc.) and language used. Innovations and techniques regarding security of online shopping are also implemented. Co-opting and invitation systems are developed, and transactions are made through third-party fiduciary deposit. Entrance fees are required from new sellers and feedback is collected via buyers’ forums.

Eventually, a search engine named Grams has also been developed. It indexes items from various platforms and increases their influence. This new Eliasian configuration reveals deep transformations within transnational criminality henceforth shifting towards new technologies. By choosing cyberspace for the implementation of their activities, these networks developed a form of « Cyberpower », as coined by Joseph Nye. In other words cybercriminality has learnt how to make the most of the web by using its specific features.

To elude national sovereignty and increase the potential of this underground economy, the cybercriminal body is mainly using Bitcoins. Completely decentralised and not bound to any official issuing institution, this currency enables relatively low-key transactions. Indeed, these transactions are registered in a block chain featuring the complete transaction history. Aware of the risks linked to such records, cybercriminals use various services to cover their identity and launder bitcoins.

Bitcoins are also subject to speculation as there is no regulation body. This gaming is materialised through mining, a type of reward allowing users to obtain money without carrying out any transaction. This tells how valuable are bitcoins to those wishing to stay out of the law. However, by trespassing on public administration responsibility over money regulation, Bitcoin is eroding state authority.

Therefore, we may understand the growing interest of various countries for Bitcoins. Nonetheless they disagree over the symbolic recognition of the currency. As Thailand had it prohibited for a long time, Germany was one of the first to acknowledge it officially. Facing their inability to fight cybercriminality in an efficient way, some countries engaged in a process of normalising Bitcoins, committing to regulate the industry and control transactions.

As to banking institutions, they are also taking Bitcoins into account and adapting to this technology. It is worth mentioning that Barclays allowed Bitcoins transactions made for charity donations. Recognition of this currency matches massive bank investments in startups of the Fintech sector, as an investment in the future. A report published on March 17th 2015 by the Juniper consultancy stated that Bitcoins should reach 5 million users before 2019.

It is worth highlighting how much this virtual currency and the Dark Web structure and support the economy of cybercriminality thanks to their inner characteristics. Being deeply intertwined, these tools speed up diffusion of criminal networks powers hardly regulated by states.

References

Even Maxence, Gery Aude, Louis-Sidney Barbara, « Monnaies virtuelles et cybercriminatilité : État des lieux et perspectives », 2014, note stratégique disponible à cette adresse :

http://www.ceis.eu/fr/system/files/attachements/note_strategique-monnaies_virtuelles_fr_0.pdf

Herlin Philippe, Apple, Bitcoin, Paypal, Google : la fin des banques ? : Comment la technologie va changer votre argent, Paris, Eyrolles, 2015.

McCusker Rob, R. (2006) « Transnational organised cybercrime: distinguishing threat from reality », Crime, Law and Social Change, 46 (4-5), 2006, p. 257-273.

Observatoire du monde cybernétique, « Cybercriminalité 2.0: guerre entre les blackmarkets », 39, juin 2015, p. 2-5.

Rosenau James N., Turbulence in World Politics: a Theory of Change and Continuity, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1990.

UIT, « Understanding Cybercrime : Phenomena, Challenges and Legal Response », septembre 2012, report available here :

http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/cyb/cybersecurity/docs/Cybercrime%20legislation%20EV6.pdf

Untersinger Martin, « Les coulisses de l’opération « Onymous » contre des dizaines de sites cachés illégaux », Le Monde, 11 novembre 2014, disponible à l’adresse suivante: http://www.lemonde.fr/pixels/article/2014/11/11/les-coulisses-de-l-operation-onymous-contre-des-dizaines-de-sites-caches-illegaux_4521827_4408996.html

Feb 2, 2016 | Africa, Diplomacy, Global Public Health, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English)

By Clément Paule

Translation: Cécile Fruteau

Passage au crible n° 134

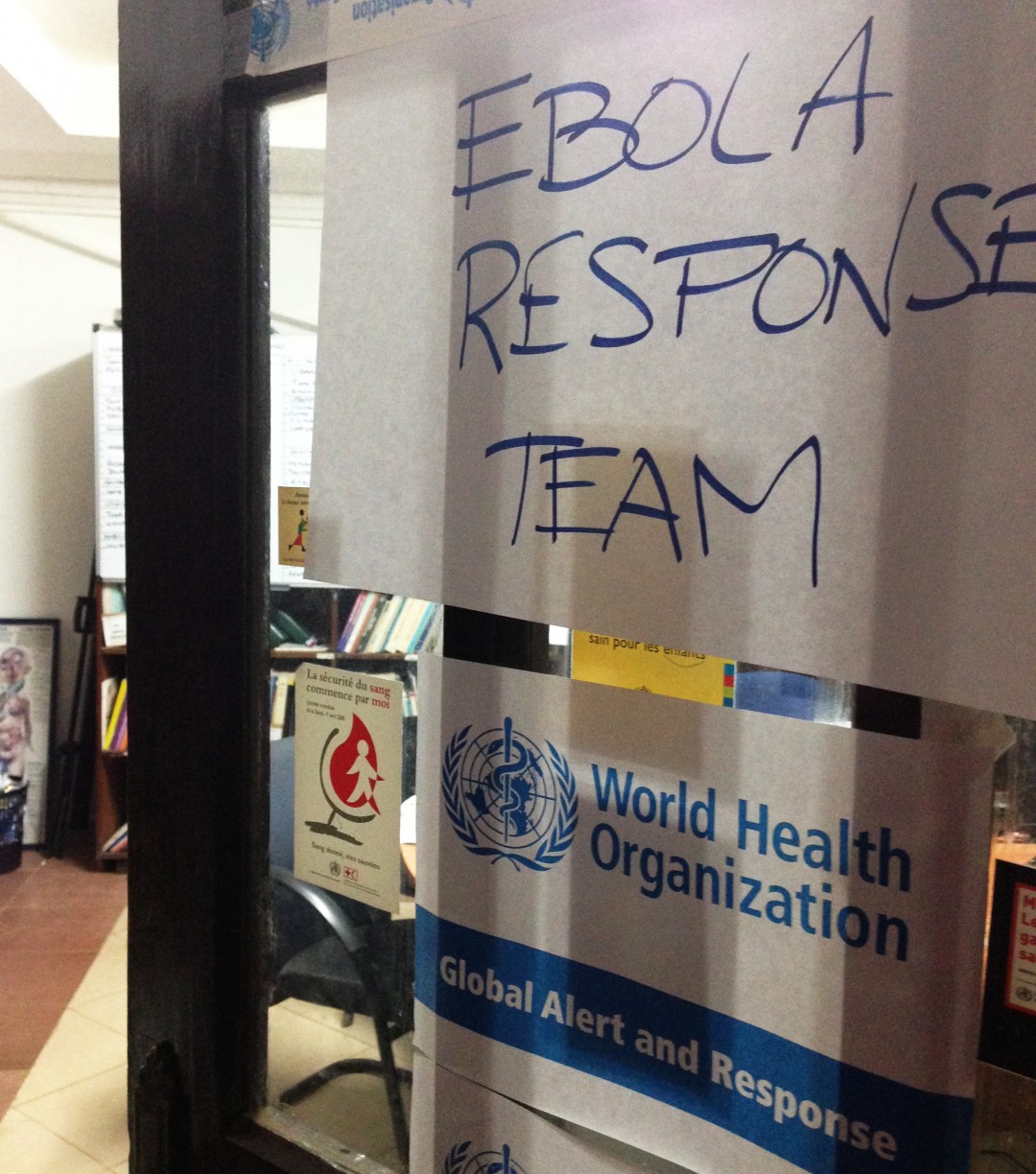

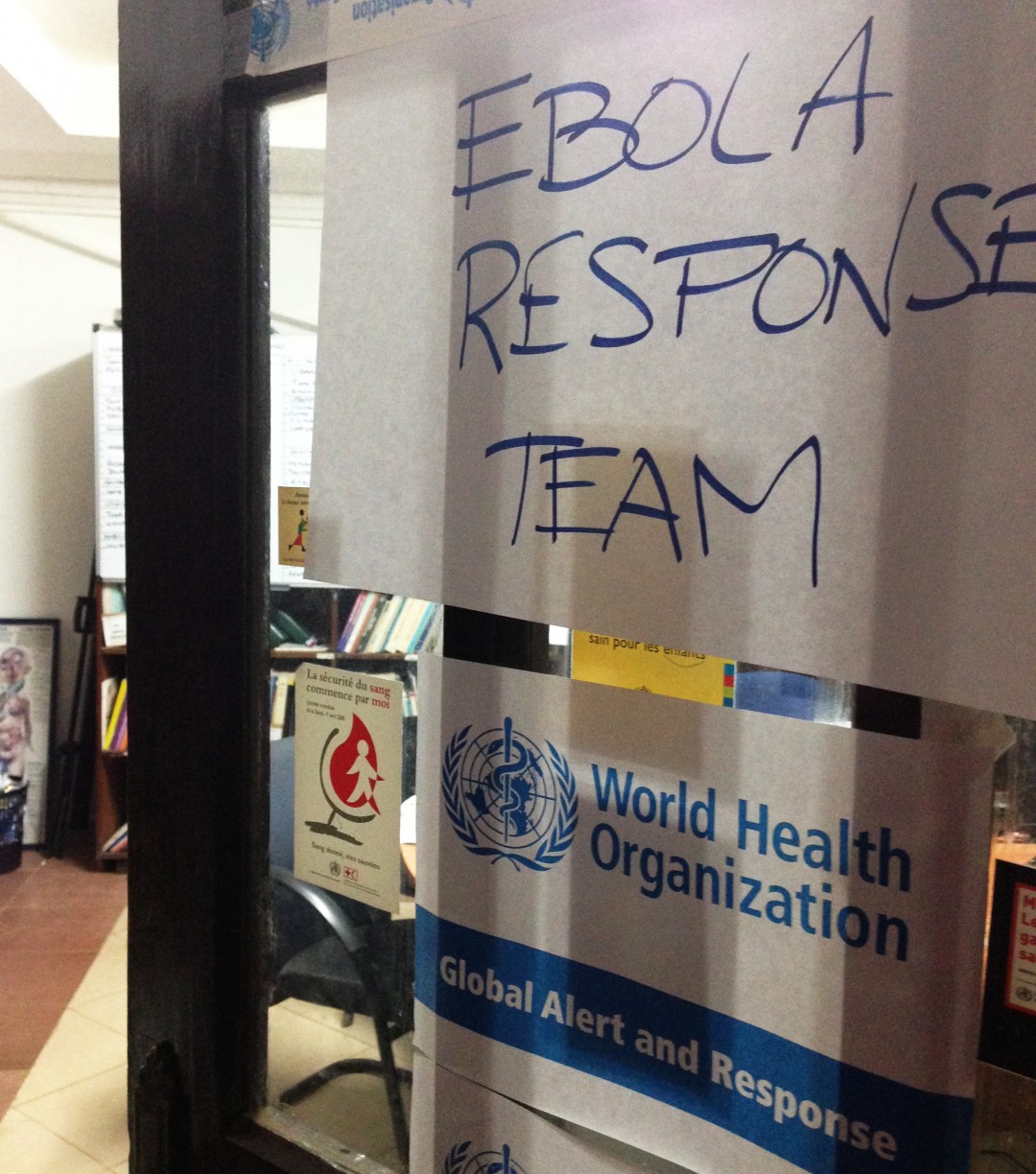

Source : Flickr CDC Global

Source : Flickr CDC Global

On September 14, 2015, the health authorities of Sierra Leone reported the death of a teenage girl infected with Ebola in Bombali, a district located in the Northern Province. Yet, during the previous six months, the area had not registered any new cases and the country had hoped to reach the forty-two days threshold without any new infections – i.e. twice the normal incubation period of the virus – that would have meant the transmission of the disease had stopped. Such resurgence is somewhat similar to what happened in Liberia where the haemorrhagic fever reappeared at the end of June 2015, one and a half months after the World Health Organisation (WHO) had declared the State “Ebola-free”. Even if the evolution of new Ebola occurrences has registered a constant decrease since its peak recorded between September and December 2014, the situation is far from being over, not when the rainy season is about to start and humanitarian funding is drying up. So far, up to 28,000 cases with 11,300 fatalities have been reported in West Africa alone and WHO estimates that such numbers are probably underestimated. Despite having weathered numerous criticisms regarding both its conduct qualified as “irresponsible” by MSF (Doctors Without Borders) and its achievement described as “a failure of dismal proportions” by the President of the World Bank, the health organisation has again taken on the supervision of the operations in August 2015.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

From the moment it was founded in 1948, WHO was meant to coordinate operations relative to public health threats. However, some elements have to be considered to better comprehend where the organisation’s claim now stands. Despite the success it registered with the eradication of the smallpox in 1980, its failed attempt at eliminating malaria as well as its lack of flexibility both weakened its influence during the following years. WHO was then regarded as a profligate and politicised institution. Only with the structural reforms undergone in the nineties, and more precisely under Dr Brundtland’s administration, was the organisation able to re-establish its leadership during the outbreaks of SARS (severe acute respiratory Syndrome) in March 2003 and of H5N1 avian influenza later on. For the latter, WHO did not hesitate to confront the Chinese Government it accused of withholding information. With a brand new Division of Communicable Diseases created in 1996 and the precious Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) set up in 2001, the organisation had the capacity to work according to the revised 2005 version of the IHR (International Health Regulation), which constitutes a legally binding instrument for all 196 States Parties. Its credibility however was again undermined by the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009 when its undue alarmism raised a new bout of criticisms and its experts were suspected of likely collusions with the pharmaceutical industry.

Such is the context when the Ebola outbreak engulfs rural areas of Guinea-Conakry, West Africa. Alerted by MSF, WHO seems to minimise the threat and implies that the spreading of the haemorrhagic fever is under control. After a deceiving weakening of the propagation of the disease in late April, Ebola amplifies again and moves to the urban spaces of Liberia and Sierra Leone in May before reaching Nigeria. Confronted with the inability for local authorities to cope with the exponentially increasing number of victims, WHO finally declares the crisis as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on May 8. This belated decision comes four and a half months after the outbreak started, at a time when waves of moral panic are forming because of discriminatory measures that in complete contradiction with the International Health Regulations. Indeed, if the unilateral closures of borders or the interruption of many air links provide the illusion of a possible containment of the disease, these actions impede the delivery of humanitarian assistance.

Theoretical framework

1. The clear failure of global governance for health. Shunned because of its inertia, WHO is not able to ensure the management of the crisis. Hence, the task goes to other actors.

2. The structural challenges of a necessary reform. After the fiasco of the summer 2014, the health organisation works to learn from the past and redefines both its operative system and priorities. However, some of the observed deficiencies result from various aspects that are directly linked to the very role of the institution.

Analysis

When the Ebola outbreak starts, non-State actors such as MSF, who work alongside national health personnel, carry out the first emergency response. Quickly overtaken by the crisis, the WHO Regional Office for Africa is so slow to react that it is accused of minimising the seriousness of the situation to accommodate some governments eager to reassure mining investors. Since the international organisation has no real communication strategy, it does not manage to coordinate its own actions with the humanitarian operations, nor does it manage to have its own regulations respected by overreacting States. In this context, the appointment of a health crisis veteran as special coordinator of the UNS (United Nations system) on August 12, 2014, indicates a change of management at its expense. A month later, the unanimous adoption of Security Council Resolution 2177 defines the outbreak as a threat to international security and leads to the adoption of the UNMEER (United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response). The constitution of this novel structure run by knowledgeable executives can be seen as a disavowal for WHO and the organisation is relegated to the sidelines. To add insult to injury, in October 2014, the institution has to face a new scandal. An internal memorandum leaks to the media. Are then disclosed some incriminating elements on the delays preceding WHO’s involvement in the crisis, its staff’s ineptitude and the politicisation of some appointments. Reported by the Associated Press agency, other documents further suggest that the organisation’s indecisions stem from concerns about possible diplomatic tensions emerging between the different affected States. Indeed, if an alarmist stance were to be adopted, it would have a likely socio-economic impact on these countries. It is also important to remember the previous controversy regarding the H1N1 influenza pandemic for it may have partially shaped the institution’s deliberated caution. In any event, and in reaction to the many criticisms, WHO convenes an extraordinary meeting in Geneva on January 25, 2015. Even though some contributors denounce the delays and failures of the international response, a resolution is unanimously adopted and reasserts the leading role of the organisation in preparing and managing health crises. The creation of a specific $100 millions fund, the deployment of a “global public health reserve force” and the use of a panel of independent experts to assess the conducted operations are part of the announced measures. In July 2015, the panel of experts does publish a report listing WHO’s many deficiencies and advocating a thorough reform of its operative norms and processes.

That being said, it is essential to review some of the constraints WHO’s actions are encountering, the first of which being its limited funding. The organisation receives $4 billions for a two-year programme, an amount that ranges far behind the $6.9 billions allocated to the American Centres for Disease Control and Preventions (CDC) for the sole year 2014 or the funds given to the Gates Foundation. Furthermore, WHO’s funding comes from voluntary contributions. These latter have reached a standstill since the financial crisis of 2008 and often limit the actions the organisation sets as priorities since the money is only allotted for specific missions (earmarking, etc.). If the institution’s limited degree of latitude results in part from both internal power struggles and a far too bureaucratic system, it also originates from its administration’s incapability to foresee the importance of the Ebola threat just because the disease had already been contained in the past. More generally, there is a discrepancy between WHOs’ claimed leadership that gives the organisation a semblance of an operational and supranational actor and its role as an agency specialised in advisory and coordination tasks. The reciprocal misconception existing between humanitarian and health actors is the best example of this disparity. In fact, the ensuing distorted perceptions about WHO give rise to sometimes misguided stigmatisations and disappointment. Hence, the health organisation’s redeployment is not just another legislative and financial reform. It implies the choosing of a new institutional identity inherited from its complex history where the organisation either becomes a full political advisor or a technical expert.

References

Guilbaud Auriane, Le Paludisme. La lutte mondiale contre un parasite résistant, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2008. Coll. Chaos International.

Lakoff Andrew, Collier Stephen J., Kelty Christopher (Éds.), « Issue Number Five: Ebola’s Ecologies », Limn, janv. 2015, consulté sur le site de Limn : http://www.limn.it [10 août 2015].

Paule Clément, « L’illusoire confinement d’une crise sanitaire. L’épidémie Ebola en Afrique de l’Ouest » in : Josepha Laroche (Éd.), Passage au crible de la scène mondiale. L’actualité internationale 2014, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2015, pp. 137-142. Coll. Chaos International.

Paule Clément, « Une remise en cause du savant et du politique. Dividendes et suspicions mondiales autour des politiques de vaccination », Passage au crible, (12), 26 janv. 2010, consultable sur le site de Chaos International :http://www.chaos-international.org

Paule Clément, « Le traitement techniciste d’un fléau mondial. La troisième Journée mondiale du paludisme, 25 avril 2010 », in : Josepha Laroche (Éd.), Passage au crible de la scène mondiale. L’actualité internationale 2009-2010, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2011, pp. 129-134. Coll. Chaos International.

Rapport du panel d’experts indépendants intitulé « Report of the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel », publié le 7 juillet 2015 et consultable sur le site de l’OMS : http://www.who.int [15 août 2015].

Jan 26, 2016 | Climate change, English, environment, Passage au crible (English), United Nations

By Stefan C. Aykut

Translation: Cécile Fruteau

Passage au crible n° 133

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia

In December 2015, Paris will host the 21st Conference of the Parties to the Climate Convention (CoP21). Great expectations surround what is advertised as the global governance’s major environmental event since the conference is supposed to secure an international agreement to cope with global warming. More than twenty years of discussions since the subject had been first broached at the Conference of Rio in 1992 were necessary to enable this issue to get its own given place on the international agenda. Yet, concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG) have set records in 2013 and the international panel of experts on climate change (IPCC)’s fifth report states that global warming is bound to exceed the additional 2°C critical threshold. Highlights on why such a dismal failure occurred.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Basically, the climate change debate went through three main phases. The first one starts with the signature of the Climate Convention in 1992 and is marked by the emergence of the climate regime. When the Berlin wall falls, a world where States cooperate with each other can indeed be envisioned. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol defines specific objectives for greenhouse gases reductions to be completed by developed countries and economies in transition alike. It also establishes three market-based flexible mechanisms enabling countries to pursue these goals at minimal costs. The second step begins in 2001 when the United States decide not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol handing any further negotiations over to the European Union. Hence, the Kyoto Protocol comes into power without the United States in 2005 whilst the less developed countries (LDC) rise and press forward matters of direct concerns to them. For instance, they are particularly concerned about finding ways to adapt to climate changes and securing the necessary technology and financial transfers enabling them to achieve economic development without heavily relying on carbon. This second phase ends up with the fiasco of the Copenhagen Climate Conference in 2009. Whereas the signing of a new treaty in lieu of the Kyoto Protocol is expected, the conference only leads to a minimal agreement, which conveys a new deal where Europe is shunned and the United States as well as emerging countries can impose their views.

Subsequently to the Copenhagen Conference, a dual imperative shapes the post 2012 period. The first goal concerns the signature of a new agreement including all State actors before 2015 for it would allow it to come into force in 2020. The second imperative is about negotiating an agreement covering the time lapse up to 2020 and preventing LCDs from interrupting their gas emission reduction efforts for lack of appropriate funding. Now at the eve of the opening of CoP21, it is important to remember that the conception of an apolitical and global governance has known many drawbacks due to events such as the US war in Iraq, the financial crisis in 2008, and the Copenhagen Conference in 2009. These latter were more or less connected to climate issues but forcefully terminated any wishful thinking on mutual and efficient ways to tackle them.

“political agreements, treaties, international organisations, legal procedures, etc.” structuring the world political stage on any given subjects (Krasner, 1983; Keohane, 1984). This concept also covers other disciplinary fields. Thus, in foucauldian work, it describes all cultural, institutional or other mechanisms constituting a “regime of truth” (Foucault, 2001: 160; Leclerc, 2001). Within the body of science and technology research, the notion includes the contemporary ways to produce scientific knowledge that are intricately linked to political and economic challenges (Gibbons et al., 1994; Pestre 2003). When applied to climate issues, these various conceptions overlap and define a multi-layered system where arenas and institutions gather an increasing number of States and stakeholders. This complex structure initiated new research practices as well as assessment and validation procedures. If it witnessed numerous clashes between opposite economic and political interests, it also led to novel connections between sciences, expertise, politics and markets.

Theoretical framework

1. Climate regime. In international relations, regime designs any “political agreements, treaties, international organisations, legal procedures, etc.” structuring the world political stage on any given subjects (Krasner, 1983; Keohane, 1984). This concept also covers other disciplinary fields. Thus, in foucauldian work, it describes all cultural, institutional or other mechanisms constituting a “regime of truth” (Foucault, 2001: 160; Leclerc, 2001). Within the body of science and technology research, the notion includes the contemporary ways to produce scientific knowledge that are intricately linked to political and economic challenges (Gibbons et al., 1994; Pestre 2003). When applied to climate issues, these various conceptions overlap and define a multi-layered system where arenas and institutions gather an increasing number of States and stakeholders. This complex structure initiated new research practices as well as assessment and validation procedures. If it witnessed numerous clashes between opposite economic and political interests, it also led to novel connections between sciences, expertise, politics and markets.

2. A “schism of reality”. German political scientist Oskar Negt (2010) introduced the notion of “schism of reality” in his reference work on political education to describe on an analytical level the early signs of serious constitutional crises that were overlooked because of a deceivable continuity in the democratic process. By analysing the paradigms of both the Roman Republic before the Principate and the Weimar Republic before the Nazis took over, Negt concludes these phases presented two forms of coexisting legitimacy. The first one is intrinsic to the democratic process and is based on rules of decorum and civility as well as on rhetoric and parliamentary debates. The second one relies on military power, violence, and the occupation of the public space. The consequent hiatus that Negt calls Wirklichkeitsspaltung or schism of reality after a concept borrowed from psychology, then gradually increases. Citizens still go out and vote whilst democratic decorum remains in place. In these conditions, perceiving any warning signs tends to be challenging.

Analysis

A similar hiatus seems to be affecting the climate governance. Historically, the schism takes place in the late nineties when the neo-conservative movement imposes its views on the United States leading them to bet on military power and to reject multilateralism processes . In 1997, the famous Byrd-Hagel resolution approved by the Senate reflects their hostility toward a treaty that would enforce constraints on Americans without implementing “comparable” pressure on LDCs (Senate 1997). At the same time, while the two Gulf wars (1990 and 2003) and the conflict in Afghanistan are raging, Washington protects American vital interests in terms of security and oil supply, enticing the American way of life to go unchanged. Neither the deeper meaning of these conflicts nor the sudden American decision to disengage from the Climate process has been substantially studied.

Such segregation in the negotiations can be analysed on a more structural level. Research on how international regimes interplay (Oberthür and Stokke, 2011) gives evidence that the Climate regime does interfere with many others, which all have their own proceedings and specialised institutions. A key component of the schism is how far removed the climate discussions are from other institutions. As a matter of fact, the World Trade Organization (WTO) does not distinguish between polluting and non-polluting activities, which contributes to a generalisation of a pro-carbon economy. Furthermore, the World Bank still heavily finances large infrastructure projects as well as an industrialisation that leaves little room for environmental concerns . Even worse, the Kyoto approach tends to separate two energy regimes: it indeed promotes discussions and measures on GHGs and CO2 thus trying to solve output issues, but it does not tackle the input aspect of the problem, namely, the extraction and burning of energy resources. By targeting gas emissions instead of addressing patterns of economy development or international trades or even global energy systems, the Climate regime only managed to build “fire walls” (Alvater, 2005: 82) isolating climate challenges from other regimes.

Hence, a schism does separate two realities. On one side stands a world of global economy and finance, unbridled exploitation of fossil energy resources and stiff competition between States. On the other side, a world of negotiations and global governance gets more and more isolated. The conference opening in Paris can only succeed if the different stakeholders acknowledge such segregation and open up the debate, finally coming to an end with their lack of awareness concerning other critical issues that have been impeding previous discussions.

References

Altvater Elmar, Das Ende des Kapitalismus, wie wir ihn kennen, Münster, Westfälisches Dampfboot, 2005.

Foucault Michel, Dits et écrits, Paris, Quarto Gallimard, 2001.

Gibbons Michael, Nowotny Helga, Limoges Camille, et al., The New Production of Knowledge. The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies, London, Sage, 1994.

Keohane Robert O., After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy, Princeton (N.J.), Princeton University Press, 1984.

Krasner Stephen D., (Éd), International Regimes, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1983.

Leclerc Gérard, « Histoire de la vérité et généalogie de l’autorité », Cahiers internationaux de sociologie, 2 (111) 2001, pp. 205-213.

Negt Oskar, Der politische Mensch. Demokratie als Lebensform, Göttingen, Steidl Verlag, 2010.

Oberthür Sebastian et Stokke Olav Schram, (Éds), Managing Institutional Complexity: Regime Interplay and Global Environmental Change, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2011.

Pestre Dominique, Science, Argent et Politique. Un essai d’interprétation, Paris, Inra, 2003.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia