Dec 22, 2012 | Development, environment, North-South, Passage au crible (English)

By Weiting Chao

Passage au crible n°80

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia

The 18th session of the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change COP 18) and the 8th session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP8) took place in Doha (Qatar) from 26th November to the 8th of December 2012. The outcome of the two-week negotiations, agreed by nearly 200 nations, extends to 2020 the Kyoto Protocol.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Signed in 1997, The Kyoto Protocol is the only global agreement which sets binding obligations on industrialized countries. It is based on the UNFCCC, signed by 153 countries in 1992, which set the goal of reducing GHG emissions (greenhouse gas emissions).

The protocol divides the countries into two groups, Annex I and Non-Annex I countries, with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and the principle of equity. In 2001, the United States pulled out of the Protocol, saying that it would damage the US economy. This decision has proved detrimental to the success of the international efforts. Therefore, the EU (European Union) has played a leading role in maintaining the ongoing negotiations.

The Protocol came into effect on 16th of February 2005, following its ratification by Russia. Since the agreement was set to expire at the end of 2012, negotiations about the post-Kyoto period have been underway since 2005. During the Bali Conference (COP13, 2007), the participating nations agreed to the Bali Road Map which set out a two-year process to finalize a binding agreement for 2009 in Copenhagen. However, there was no significant progress and only a diluted version of the agreement was achieved. Indeed, as the Copenhagen Accord was not legally binding, it did not commit countries to agree to a new binding text. In 2011, Russia, Japan and Canada confirmed they would not participate in a second round of emission reductions under the new Kyoto Protocol. Further, the United States reaffirmed their commitment to stay out of the treaty. In 2011, at the Durban Climate Change Conference, a subsidiary body was established: it was an ad hoc Working Group, part of the Durban Platform for enhanced action set up to drive the development of another document. The adoption of a universal agreement on this issue was postponed to 2015, with expected implementation in 2020. In 2011, at the Durban Conference on Climate Change in Doha, however, negotiations led to a simple extension of the Kyoto Protocol until 2020.

Theoretical framework

1. Procrastination as a negotiation technique. Postponing the signing of a settlement ad libitum, while extending talks, is a well-known diplomatic strategy. The parties can hold up negotiations if they do not want any agreements to be reached.

2. The persistence of the North-South divide. After two decades of negotiations the difficulties between developed and developing countries have worsened considerably because of climate change, making the signing of any new treaty more difficult to achieve.

Analysis

The Doha agreement is designed to be a tool to resolve the problem of global warming governance. But in reality it only helps to keep the protocol and ensure that negotiations continue to take place. The second period of the Protocol commits the EU, Australia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, Ukraine, and Monaco to another 8 years (1 January 2013 to 31 December 2020). But these countries account for only 15% of global GHG emissions. In addition, they have disparate commitments ranging from a 20% reduction on emissions levels from 1990 for the EU to a decrease of only 0.5% compared to 2000 levels for Australia. Finally, this arrangement does not commit the United States, Canada, Japan, Russia, New Zealand and other emerging countries. However, at the very least, the agreement buys participants more time to implement policies against global warming. In other words, developing countries and countries outside the Kyoto Protocol can still enjoy a secure benefit until 2020. The failure of the first sequence of Kyoto and the withdrawal of United States emphasizes the considerable number of “free riders” who wish to evade the constraints of collective action (Olson). However, when a key player retires, it can be detrimental not only to the other participants but also to the success of the whole arrangement. A second problem is also caused if all stakeholders reject the implementation of the Treaty this would lead to an outright cancellation of the whole agreement. Parties tend to oscillate between these two scenarios because they believe that non-completion is ultimately the strategy that best suits their individual needs. Recent negotiations have been postponed to the post-Kyoto period, as participants remain uncertain about the costs and benefits of such an agreement. Accurate forecasting can be difficult: it can lead to, for example, an underestimation of the future costs. Moreover, parties tend to delay and wait to see how others engage with the agreement. All these factors lead to a state of procrastination. Even though numerous scientific studies have recently shown how the climate might deteriorate more quickly than expected, this policy of procrastination could lead to a major ecological disaster. In other words, the harmful policies of stowaways are already at work.

The conflict between developing countries and industrialized countries forms a central element of environmental governance. Therefore, the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities was recognized in 1992. This principle allows developing countries to increase their emissions to ensure their economic development. However, since some of them have emerged as BASIC countries (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China), the traditional North-South divide has intensified. It is also particularly complicated because China has now become the biggest CO2 emitter in the world, surpassing the emissions of the United States in 2006. During the post-Kyoto negotiations, many developed countries in the UNFCCC – including the United States and Australia – have therefore advocated the replacement of the Kyoto Protocol by a new text, which also includes the commitment of many of the countries of Annex I and developing countries. But for now, developing countries still refuse to accept any obstacle to their development. They demand that developed countries take the lead in a substantial reduction of GHG emissions.

We can see that there is little progress in the fight against global warming. The extension of the Kyoto Protocol only allows the negotiations to continue. To reach a real agreement and prevent an ecological disaster, states should abandon their strategy of procrastination, such as bringing NGOs into discussions. The EU, the U.S. and the BASIC need to play a role in the adoption of a new protocol. If the EU implements emission reductions, the United States and other emerging countries such as China cannot escape the “prisoner’s dilemma” of climate change.

References

Akerlof, George. A, « Procrastination and Obedience », American Economic Review, 81 (2), 1991, 1-19.

Churchman, David, Negotiation: Process, Tactics, Theory, (2nd Ed.), Boston, University Press of America, 1997.

Kontinen Tiina, Irmeli Mustalahti, « Reframing Sustainability? Climate Change and North-South Dynamics », Forum for Development Studies, 39 (1), mars 2012, 1-4.

Olson Mancur, Logic of Collective Action, Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard University Press, 1965.

Timmons Roberts J., Parks Bradley, A Climate Of Injustice: Global Inequality, North-South Politics, and Climate Policy, The MIT Press, 2006.Site de COP18: http://www.cop18.qa [15 décembre 2012].

Uzenat Simon, « Un multilatéralisme sans contraintes. Les engagements des États dans le cadre de Copenhague », Passage au crible, (15), 18 fév. 2010.

Dec 22, 2012 | Articles, Fil d'Ariane, Publications (English)

Par Daniel Drache

Abstract

Canada has been both blessed and cursed by its vast resource wealth. Immense resource riches sends the wrong message to the political class that thinking and planning for tomorrow is unnecessary when record high global prices drive economic development at a frenetic pace. Short-termism, the loss of manufacturing competitiveness (‘the dutch disease’) and long term rent seeking behaviour from the corporate sector become, by default, the low policy standard. The paper contends that Canada is not a simple offshoot of Anglo-American, hyper- commercial capitalism but is subject to the recurring dynamics of social Canada and for this reason the Northern market model of capitalism needs its own theoretical articulation. Its distinguishing characteristic is that there is a large and growing role for mixed goods and non-negotiable goods in comparison to the United States even when the proactive role of the Canadian state had its wings clipped to a degree that stunned many observers. The paper also examines the uncoupling of Canadian and American economies driven in part by the global resource boom. The downside of the new staples export strategy is that hundreds of thousands of jobs have disappeared from Ontario and Quebec. Ontario, once the rich have province of Confederation, is now a poor cousin eligible for equalization payments. Unlike earlier waves of deindustrialization, there is little prospect for recovering many of these better paying positions. Without a focused government strategy, the future for Canada’s factory economy is grim. The final section addresses the dynamics of growing income polarization and its lessons for the future. With a global slowdown or worse on the horizon Canada’s unique combination of mixed goods and orthodox market-based policies is likely to be unsustainable in its current form. For countries with a similar endowment the Northern model is unexportable.

Télécharger l’article Canada’s Resource Curse: Too Much of a Good Thing

Dec 9, 2012 | European Union, Passage au crible (English), Peace, UN

By Josepha Laroche

Translation: Pierre Chabal

Passage au crible n°79

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

On 29 November 2012, Palestine became a non-State member of the UN, thus benefiting from the same status as the Vatican. 138 states voted in favor of its candidacy, allowing it to move from the status of “entity” to that of “Non-member State” and thus finalize the formal request by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas from the rostrum of the United Nations on September 24, 2011.

41 States chose to abstain, while 9 countries voted against. These include the United States, Israel, the Czech Republic, Canada and five micro-States: Marshall Islands, Micronesia, the Republics of Nauru, Palau and Panama.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Symbolically, this vote took place sixty-five years to the day after the adoption of the partition plan of Palestine. Indeed, on 29 November 1947, the UN voted for this text establishing a “Jewish state” and an “Arab State” and conferring international status to Jerusalem. The British mandate, which had begun in 1920, thus ended in 1948. But that year is also marked by the creation of the State of Israel (May 14) and the outbreak of the first Arab-Israeli conflict. After the Six-Day War (5-10 June 1967) – which brought head to head Israel and Egypt, Jordan and Syria -, Israel conquered the West Bank and Gaza. The Jewish state also took the Old City of Jerusalem which then became its capital, but many states did not recognize this latest initiative. The UN then passed, on 22 November 1967, the famous resolution 242. Reaffirming “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territories by war and the necessity to work for a just and lasting peace enabling every State in the area to live in security”, this Resolution certainly realized a clever compromise between differing claims, but its inherent ambiguities would not facilitate the elaboration of a future settlement. In October 1973 (6-24 October), Israel won the Yom Kippur War, also called the October War or the Arab-Israeli War that had brought it in confrontation with a coalition led by Egypt and Syria. More generally, one of the consequences of this conflict was the oil crisis of 1973, when in retaliation to Israel’s allies, the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) decided to increase by 70% the price of the oil barrel, while reducing its production. In 1974, the PLO (Organization for the Liberation of Palestine) was admitted to the UN with observer status. Then, a few years later, the Palestinian National Council – the legislative body of the PLO – proclaimed in Algiers the independence of a State of Palestine on 15 November 1988, following the liberation of the West Bank area (which was occupied by Jordan since 1948). But this statement was not accompanied by any de facto independence although the United Nations considers as legitimate “Palestinian territories” the two areas located on either side of the State of Israel: the Gaza Strip in the West and the West Bank in the East. It was not until 13 September 1993, though, that Israel and the PLO recognized each other and signed the Oslo Interim Agreements. These aim to expand Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza and to provide for a democratically elected Council that is to supersede the Israeli military and civilian authorities. These agreements also indicate that Israel will continue to control the external security and the protection of Israelis. However, their implementation has kept on proving difficult. The creation of a Palestinian state, under the Oslo Agreements, should have seen light in 1998 according to modalities jointly elaborated by the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority but this did not happen. In addition, Israel went on building settlements, despite the disapproval of the European Union and of the United States. On 25 March 1999, the European Union spoke in favor of the Palestinians’ right to self-determination and statehood. On 9 January 2005, Mahmoud Abbas was elected president of the Palestinian Authority. On 12 September, all Israeli settlements in Gaza were dismantled and the last Israeli soldiers withdrew. Control of the entire territory of Gaza then returned to the police forces of the Palestinian Authority, while the president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, underlined he intended to bring forward the project of a Palestinian state. But on 12 and 14 June 2007, Hamas drove the PLO away from Gaza, challenging Abbas’ presidential power and more generally opposing the Fatah forces. In other words, against Israel, representatives of the Palestinian people appear completely divided: to Hamas, the Gaza Strip; and to the Palestinian Authority, the West Bank.

Theoretical framework

1. The absence of a European diplomacy. The EU Member-States have spoken in a disorderly manner on this crucial issue. In so doing, being so divided, they have demonstrated the absence of any European diplomacy as to an issue that is yet a major one for world peace.

2. The deadly spiral of coercive diplomacy. On the occasion of this issue, Israeli diplomacy has refused to incorporate the Palestinians’ wish for recognition. Exclusively defined in terms of strategy, such diplomacy neglects however, the symbolic dynamics this new status can launch.

Analysis

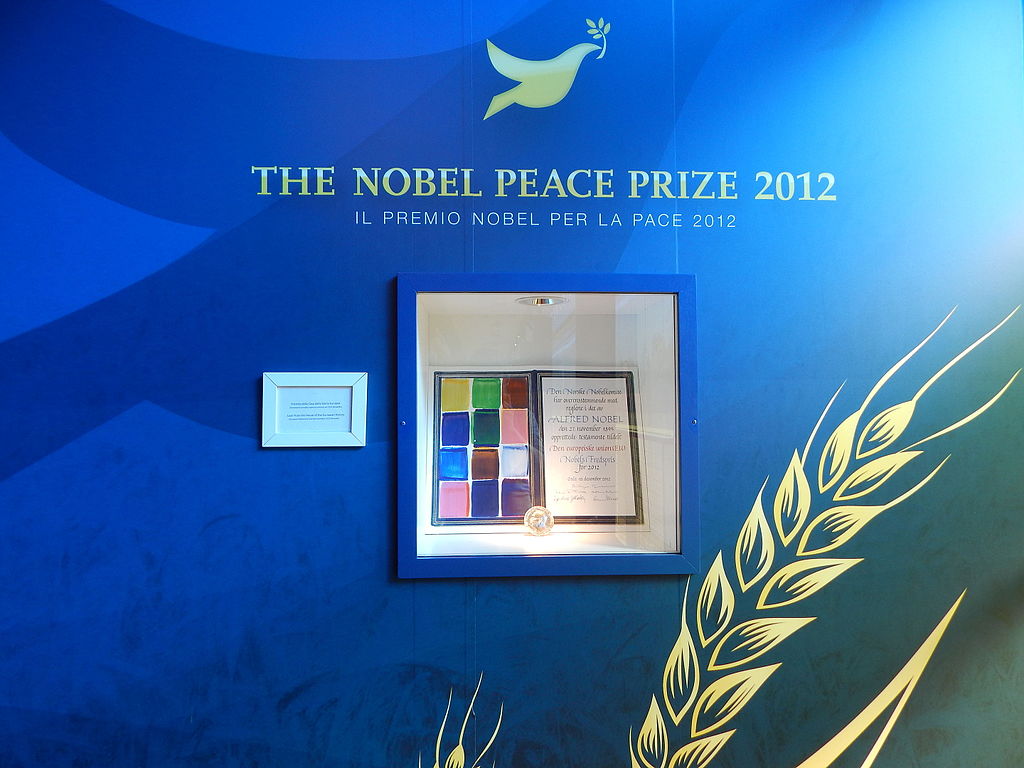

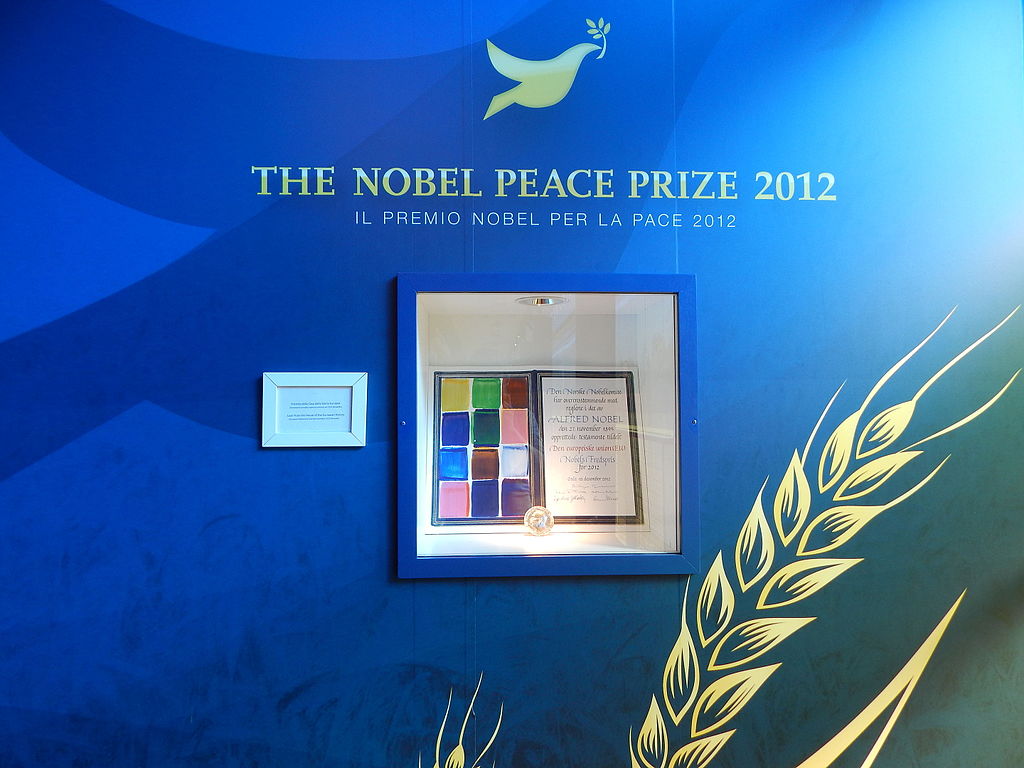

If the Nobel Peace Prize awarded on December 10, 2012 to the European Union underlines well the ‘performative authority’ of the Nobel diplomacy, it however cruelly highlights the inconsistency of European diplomacy. In fact, for the European Union to finally become a global player, the path seems still long and difficult. On the occasion of this historic vote, did one not notice abstentions by the following EU Member-States: Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania and the United Kingdom? Even though the Czech Republic decided to align onto the Israeli positions, France, Spain, Italy, Sweden and ten other European countries chose, for their part, to side with the Palestinians.

Faced with such scattered support towards Palestine on the one hand, and the unwavering support of the United States on the other hand, Israel could all the more easily carry out severe reprisals against Palestine as soon as the vote was adopted. The Jewish state in effect disclosed immediately a new construction project of colonies (3,000 new homes) in an area hitherto free of all occupation. This project thus undermined the very viability of the Palestinian state. In addition, the Israeli government – which is preparing new elections – decided to confiscate the income from taxes levied on goods imported in Palestine, taxes which Israel had until then collected on behalf of the Palestinian Authority and had always transferred back to the P.A. In fact, this decision comes down to economically asphyxiate an already very vulnerable territory. This economic and financial warfare reflects a diplomatic escalation mainly based on pure force, in brief on hard power. However, it is not certain that eventually this approach proves rationally relevant for Israel.

To be sure, this new status of Palestine in the United Nations will from now on enable Palestine, if necessary, to file a complaint against Israel to the ICC (International Criminal Court). Therefore, the Palestinians will be able to argue that an occupation must be seen as a “war crime”. Finally, they will also have the opportunity to seek full membership in the UN specialized agencies (WHO, FAO, etc.). But this is perhaps not the most important point. The most important point lies primarily in the symbolic potential released by this new status, which opens up and multiplies perspectives of reconfiguration of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a way where the Israeli hard power will soon show its limits.

References

Finkelstein Norman G., Tuer l’espoir : Introduction au conflit israélo-palestinien, Paris, Aden éditions, 2003.

Laroche Josepha, La Brutalisation du monde, du retrait des États à la décivilisation, Montréal, liber, 2012.

Lindemann Thomas, Sauver la face, sauver la paix, sociologie constructiviste des crises internationales, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2010. Coll. Chaos International.

Quigley John, The Statehood of Palestine: International Law in the Middle East Conflict, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010,

Schelling Thomas, Arms and Influence, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1966.

Schelling Thomas, La Stratégie du Conflit, Paris, PUF, 1986.

Nov 9, 2012 | environment, Global Public Health, Passage au crible (English)

By Clément Paule

Translation: Pierre Chabal

Passage au crible n°78

Source : Wikipedia

Source : Wikipedia

Published on September 19, 2012, the study led by Gilles-Eric Séralini – professor of molecular biology at the Caen University, France – revived the debate on GMOs (Genetically Modified Organisms) and their use in the food industry. The findings of this research, to be sure, point to the toxicity of two chemicals produced by the Monsanto firm: the pesticide Roundup and the GM corn NK 603. These results, however, have been questioned by a large portion of the scientific community, which pointed out the statistical and methodological weaknesses of the demonstration. Some commentators have even mentioned the potential conflicts of interest of a survey funded by an association known for its militant positions. In addition, several French organizations – such as the HCB (Haut Conseil des Biotechnologies) and HANDLE (National Agency for Food Safety, Environment and Labor) – as well as some international organizations – such as EFSA (European Food Security Authority) or the German and Australian health agencies – have successively invalidated the investigations by Prof. Séralini and his team. Let us note that this controversy quickly involved many political actors – including four former Environment Ministers – and many actors from associations, across national borders. The need to assess, over the long term, the impact of transgenic plants was therefore reiterated in policymakers’ agendas, opening up the prospect of more stringent regulations at the European level.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

The first genetic manipulation took place in the early 70s, leading a decade later to pioneering GMO crops. These technical advances have stimulated large private investments in biotechnology. Mainly used by pharmaceutical companies, applications of transgenesis quickly spread to agriculture under the aegis of transnational companies such as Monsanto and Bayer. In this regard, special notice ought to be paid to the introduction on the market in 1994 of the Flavr Savr tomato, the first genetically modified food to obtain the approval of the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) in the United States. More generally, the agrochemical industry born out of the Green Revolution, until then specialized in inputs – pesticides and herbicides – has now been redeployed in the production of transgenic seeds widely used throughout the American continent. According to the ISAAA (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications) – lobbying organizations in favour of plant biotechnology -, 160 million hectares are said to be concerned today by these techniques – against 1.7 million in 1996 – a total area in increase by 8 % in 2011 alone. If these figures seem overestimated according to Greenpeace, one must nevertheless note that the share of GM corn grown in the United States, estimated at 30 % in 1998, reached 85 % in 2009.

In this logic, this model of agriculture has spread in so-called emerging countries as shown by the emblematic example of soybeans in Brazil and Argentina. The exponential growth of agricultural and food biotechnology has benefited in this respect from a lack of real control until the early 90s. However, the occurrence of repeated health crises in Western states – such as BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) – has caused the rise of citizen mobilization of transnational magnitude – from consumer associations to NGOs (Non governmental Organisations) – as well as the strengthening of legislation implemented by specialized agencies. GMOs then appeared as a public problem in several European countries. Evidence of this is the de facto moratorium on the commercialization of genetically modified products, adopted by the European Union (EU) on behalf of the precautionary principle from June 1999 to May 2004. Let us finally mention, on the international scale, the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety – relative to the Convention on Biological Diversity of 1992 – entered into force in 2003, which counts 164 signatories (but neither the United States nor Canada).

Theoretical framework

1. Internationalisation of a socio-technical controversy. Marked by considerable uncertainty, questioning about GMOs in the food industry seems to embody these difficult-to-govern situations where politics tends to be lagging behind. Therefore, the expertise plays a determining role in regulating a sector with global implications.

2. Construction of an alarm-launching vehicle. In this sense, studies involving transgenic products make up as many tactical moves whose effects can be measured especially in their multiple social usages, largely beyond the sole scientific field.

Analysis

The controversy about plant biotechnology is thus characterized above all by its complexity as it involves many actors located at different levels. Production and dissemination of GMOs are controlled and supported by the oligopolistic group of agrochemicals firms, essentially in the USA – Monsanto, DuPont, Dow AgroSciences LLC – and in Europe – Bayer Cropscience, BASF or Syngenta. Clearly, the economic dimension is fundamental here both in the commercial war being waged by the U.S. and the EU in the WTO (World Trade Organization) and in the domination over the DP (Developing Countries) which import these farming techniques. But this economic dimension cannot be separated from the health and environmental issues, defended by militant networks and by some governments. In this case, the intricacy of these different issues allows us to deconstruct the legitimacy strategies resorted to by industry managers. Let us quote the humanitarian argument presenting GM foods – including the initiative of Golden Rice – as a pragmatic solution to chronic malnutrition ravaging the South. Even though the producers of seeds have sought in parallel to protect their patents by relying on Agreements on Intellectual Property Related to Commerce and through the development of the Terminator gene, a method not commercialised for the time being.

Overall, these multiple arenas of conflict reveal the dynamics of transnationalization of a controversy that presents itself differently from one state to the next. If GM foods constitute a public problem in many European countries – including France, Greece or Austria – they are considered in substance equivalent to other products by the FDA. In this sense, the principle of precaution makes full sense within the EU, justifying restrictive regulations in terms of traceability and labelling. Conversely, these requirements do not exist in the United States as shown by Proposal 37 in California. In the absence of a consensus as to the long-term safety of these products, politicians often fall back on strategies of blame avoidance characterized by the transfer of responsibilities onto experts. As the debate grows on GM foods, symbolic actions – like those by the volunteer reapers in France – also tend to give way to a technicalisation of the controversy.

In this respect it is important to circumvent the impact of scientific studies: released in 1999, Prof. Losey’s research on the toxicity of a Bt-type corn for the monarch butterfly was used to justify the European moratorium on the extension of cultivation and marketing of GMOs. With regard to the research lead by Prof. Séralini, let us note that this is a real communication campaign. Indeed, the results were sent to a part of the French press two weeks before their official release, with a confidentiality clause. The media coverage then proved all the more sensationalist since journalists were unable to refer to other scientific opinion. Then, two books and a documentary accompanied the publication of the article by Prof. Séralini, dedicating his position as alarm-signal and ensuring the success of the mobilization despite the almost unanimous disapproval of his peers. As such, the very concept of ‘assessment’ appears here redefined, to the extent that we are witnessing a militant reconfiguration of its limits and of its role. Beyond recurrent stigmatisations affecting potential conflicts of interest, this activity primarily located between power and knowledge helps to redefine politically issues neglected by the authorities.

References

« OGM : comment ils conquièrent le monde », Alternatives internationales (43), juin 2009.

Bérard Yann, Crespin Renaud (Éds.), Aux Frontières de l’expertise. Dialogues entre savoirs et pouvoirs, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2010. Coll. « Res Publica ».

Kempf Hervé, La Guerre secrète des OGM, Paris, Seuil, 2003.

Oct 28, 2012 | European Union, Nobel Peace Prize, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English)

By Josepha Laroche

Translation: Pierre Chabal

Passage au crible n°77

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

On Friday 12 October 2012, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the European Union. The Chairman of the Nobel Committee, Thorbjorn Jagland, stated in his proclamation speech that “The EU and its ancestors have contributed for more than six decades to the promotion of peace, reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe”.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

In his will of 27 November 1895, Alfred Nobel, the Swedish chemist, industrialist and philanthropist, laid the foundation of an international system of rewards that was to be resolutely pacifist and cosmopolitan. His will comprised the creation of five annual prizes 1- all of which must equally contribute to pacifying the world stage – Physics, Chemistry, Physiology-Medicine and Literature – as well as a Peace Prize whose attribution he required be entrusted to the Norwegian Parliament (the Storting). At the time, this will aroused a deep disapproval in Sweden because Norway was then placed under the authority of Stockholm. But the activity which the Storting had already deployed in favour of peace appeared to the inventor of dynamite more important than the conflict within the Union between Norway and Sweden. A liberal and a democrat, Nobel thus expressly designated this Chamber to manage the awarding of this prize, believing that it was the best qualified and most legitimate institution. Since 1901 and the awarding of the first prizes, it is therefore a committee emanating from the Norwegian parliament in Oslo that rewards an individual or an organization which has worked particularly in favour of peace. Paradoxically, it is in Norway, one of the most Euro sceptic countries today that this prize was awarded to Europe.

As regards the prize for peace, the Swedish philanthropist did not indicate specific selection criteria. He simply outlined three main directions: “One must have worked for fraternity among nations, for the abolition or the reduction of armed forces and for the holding and the promotion of peace conferences”, he wrote. However, we can distinguish four ideal-types of recipients who participated in the development and implementation of a Nobel diplomacy. 1) Pacifist and humanitarian activism. 2) Peace through law. 3) Missionary Volunteering. 4) Expertise at the service of peace. However, obviously, the Nobel Prize awarded to the European Union does not enter into any of these categories. Yet, these have structured, for over a century, the policy of awarding the Nobel Peace Prize. How then is one to analyze this nobelisation?

Theoretical framework

1. Performative authority. We owe the concept of performative utterance to the linguist Austin. Unlike a descriptive statement such as “it is raining”, a performative utterance generates practical effects as it holds in itself the possibility to alter reality due to the institutional status of one who produces it and as a consequence due to the authority it has.

2. A window of political opportunity. This term, coined originally by John Kingdon, refers by analogy to the idea of a “window of opportunity”, a very special situation. Indeed, a situation that appears – at some point – conducive to the attainment of a political action. It represents the relevant sequence which allows taking measures that would have no chance to exist otherwise.

Analysis

This policy of allocation of the Nobel prizes has sought for over a century to contain the brutalization of the world. In doing so, it is at the origin of a coherent diplomacy by which the Nobel system intervenes globally on the world stage to impose the irreducibility of values such as freedom or democracy. Let us recall that the Nobel system is a comprehensive one that has developed over time, a non-state diplomacy which has created supports, protects and enshrines certain political processes in order to uphold its priorities and agenda on the world stage. In this case, we are dealing with an innovative diplomacy that designs norms and gives itself the means to deal with international issues considered as priorities. There also appears as an interventionist diplomacy which interferes when applicable into the internal affairs of States or into inter-state relations, regional and international disputes. Finally, an unusual diplomacy is affirming itself, powerful enough to now be able to exercise a performative authority. Therefore, why wondering that it seeks to get involved in the issues of the century by nobelising the European Union?

Because this diplomacy seeks to state the forms of the future peace, it irrupts more and more frequently into High Politics, thus determining a new mode of enunciation politics. The institution and its awardees consider themselves, in this respect, as the strongest defenders of human rights against the Raison d’Etat. By coming across as a universal power of criticism, they intervene more and more often in the international arena, whether addressing societal issues or managing more directly political issues. In doing so, they do not hesitate to interfere in the internal affairs of States or to engage in international regulations. They then deploy their actions in all directions to promote a policy which they label in the name of knowledge or common property of which they proclaim themselves the guardians.

With this award, a new doctrinal line appears that confirms the grandiose ambition which had already been sketched in 2009, when awarding the Nobel for Peace to President Barack Obama. Nobel diplomacy is indeed now powerful enough at the symbolic level to be able to exercise performative authority. In this case, the question is not whether the European institution deserves or does not deserve the prize since we are no longer there in the register of moral and good sentiments, but clearly in that of politics.

Admittedly, by nobelising the EU, the Committee has rewarded an already-achieved trajectory of peace. Similarly, it wanted to encourage and support the Union by giving it a significant trump card in the face of current difficulties and criticism. The jury thus underlined that the prize was purposefully awarded to a Europe in crisis and “experiencing severe economic hardship and social unrest”. With the Nobel and all the decorum associated with it, the Committee chose to distinguish Europe among other potential recipients in order to confer greater legitimacy worldwide. Therefore, the European Union is now the custodian of Nobel aura and values. The EU bears a project of universality that transcends it and embodies the Nobel diplomacy instead of simply being the architect of the European construction. At a time when it is so criticized and weakened, this is a political bias in its favour that is clear and simple. In this regard, this choice corresponds very closely to the designs of the great European who Alfred Nobel was, because it is a symbolic and political investment that adds credentials to the integration process. Naturally, this also constitutes a risk since the Nobel system commits all of its credit, both symbolic and institutional. In the near future, this symbolic coup could for example make it easier for the EU to claim a seat on the Security Council of the UN. Also, this nobelisation gives the EU additional authority to restore social peace in the Member States tempted by a lesser communitarism and by populist discourses, as it implicitly points to public opinions, prone to be forgetful, all that the European construction has brought them. Finally, it gives the Union a valuable symbolic resource at a time when there is talk that the ECB support the mechanisms of stability and of financial solidarity, common budgetary surveillance, and soon the Banking Union, or even a budget designed to relaunch growth for the Euro zone. In short, at a time when Europe is on the verge of becoming an integrated federal entity, the Nobel diplomacy seized a window of political opportunity to order the world by norming Europe. In other words, the prize is far from being a mere reward. It is more clearly a marching order through which the EU is mandated by the Committee to effectively accomplish and carry institutionally everything on which the EU has been engaged up till now. That is why this Nobel can be read in many ways, as a burden, an obligation of result by which the Nobel institution commands the Union to at last realize the European dream: nobelisation oblige !

References

Austin, Quand dire, c’est faire, trad., Paris, Seuil, 1972.

Cobb Roger, Elder Charles, Participation in American Politics. The Dynamics of Agenda Building, Boston, Allyn and Bacon, 1972.

Kingdon John W., Agenda, alternatives and Public Policies, 2nd ed., New York, Longman, 2003.

Laroche Josepha, La Brutalisation du monde, du retrait des États à la décivilisation, Montréal, Liber, 2012.

Laroche Josepha, Les Prix Nobel, sociologie d’une élite transnationale, Montréal, Liber 2012.

Laroche Josepha,

http://www.chaos-international.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=107%3Aune-injonction-symbolique-le-prix-nobel-de-la-paix-decerne-a-barack-obama&catid=40%3Aliste-des-passages-au-crible&directory=64&lang=f

1. In order to more accurately perpetuate the concerns of A. Nobel, the Bank of Sweden has founded in 1968 – on the occasion of its tercentenary and in the Memory of Nobel – a sixth prize: that for economics. Awarded since 1969, it still however seems singular because it is the only Nobel that crowns a social science. It is even to this day the only internationally determinant distinction in this field of research.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia