Oct 23, 2013 | Africa, Human rights, International Justice, Passage au crible (English)

By Yves Poirmeur

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n°94

Pixabay

The trial of Kenyan vice president, William Ruto, began in front of the ICC (International Criminal Court) on September 10, 2013. The same will be true for the Kenyan president, Uhuru Kenyatta, on November 12. Both cases seek to judge the alleged responsibility of the accused in the post-presidential election violence of 2007. Convened October 11-12, 2013, in Addis Ababa, the AU (African Union) requested that the UN Security Council adjourn the Kenyan affair for one year (ICC Statue, article 16). Rather than putting their threat into action to adopt a resolution calling the 34 African States to withdraw, the Union preferred to take diplomatic steps to amend the Rome Statute whose 27th article provides that no official capacity – notably one pertaining to a head of State – or immunity can be opposed to the ICC.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

By the authorization of Trial Chamber II, accorded on March 31, 2010, the prosecutor of the ICC opened an investigation of the politic0-ethnic violence, which resulted in the death of 1200 victims and the displacement of 300,000 persons in the Rift Valley. Six Kenyan figures accused of having committed crimes against humanity were summoned. Among them were three members of the union and reconciliation government: U. Kennyatta, Vice Prime Minister and Finance Minister, W. Ruto, Minister of Higher Education and H. Kiprono Kosgey, Minister of Industrialization. Elected president and vice president of the Republic in 2013, U. Kennyata and W. Ruto justify their democratic legitimacy and the sovereignty of the people in order to ask for modifications of the proceedings. They demand that their trial be postponed, or even closed definitively. The Court having rejected the majority of these demands, Kenya has brandished verbal threats to withdraw from the Rome Statute and has obtained the right to hold a summit of the AU on the “relationship between Africa and the ICC” in order to officially procure its support.

The originality of this case fits into a recurring theme of conflict between the AU and the ICC. This conflict is about the state’s obligation to cooperate with the Court when seized by the Security Council – or as in the present case by its prosecutor – due to the inaction of state-run justice (Statute, article 13). Moreover, the exacerbation of the resistance generated by the fight against impunity renders this case a symbolic one. In order to protect the accused from justice, their supporters toughen the critiques designed to discredit the ICC. It is this very behavior that the sitting president of the AU, Hailé Mariam Dessalegn, did not hesitate to bring into question as she rebuked the international court of leading a “racially-motivated pursuit of Africans” which the AU presented as a threat “to the current efforts aiming to promote peace, national reconciliation as well as the Rule of Law and stability not only in Kenya, but also in the entire sub-region”. More insidiously, these detractors are using their potential retreat from the Rome Statue as an instrument to put political pressure on the procedures of subsequent trials concerning diplomatic maneuvers. This strategy is challenged by numerous humanitarian NGOs – to which the emergence of the ICC owes much – as well as by African personalities. Said personalities underline the inexactitude of the accusations uttered against the Court, by specifying that it was under the influence of African states in five of eight affairs that it treated on the continent: the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Uganda and Mali. They are otherwise contesting the Court’s imperialist and racist character by recalling, as Amnesty International has done, that “its prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, is from the Gambia and that four of its eighteen judges come from African countries”. Furthermore, they are alerting the public opinion in Africa of the dangers of leaving the ICC – just as Desmond Tutu the South African winner of the Nobel Peace Prize did. Indeed, such a decision would allow certain leaders to continue their criminal activities with complete impunity, which would make Africa a “more dangerous place”.

Theoretical framework

1. The return of the Raison d’Etat. The fundamental principals defended by the ICC mark a crumbling of the National Interest which must henceforth give way to the demands of justice. However, the arguments to support the request for deferral of judicial proceedings, on the contrary, show its resurgence. Thus, they enforce the necessity to fill the constitutional responsibilities, to ensure the functioning of the state and to direct national and regional affairs. Finally, in reference to the recent terrorist attack in Nairobi, “necessary time to improve the efforts begun in the fight against terror and other forms of insecurity in the region” should be taken. Ultimately, demanding a revision of the Rome Statute (article 27), in order to restore the classical system of immunity behind which an unpunished criminality continues to prosper, remains the most symbolic indicator of the return of National Interest.

2. African States’ interest in a transnationalization of criminal justice. The AU’s aggressive decisions against the ICC cannot hide the real interest that the African states have in it. Not only are many of them members of the AU, but they are also often at the origin of the claims of jurisdiction. What is more, they offer important symbolic profits. Thus, can they present themselves as democracies that respect a universal moral, combatting impunity? Equally, do they draw considerable concrete advantages related to the intervention of international jurisdiction in the resolution of conflicts, the restoration of peace and the exercise of power? In doing so, they are offered the opportunity 1) to outsource the most political justice, 2) to take victims’ rights into account so that justice can be served and 3) to facilitate a process of reconciliation thanks to the arrest of presumed criminals and to their delocalized judgment, all guaranties for a fair trial.

Analysis

In the face of different jurisdictions of the ICC, the AU adopts two different attitudes. Regarding the pursuits triggered by non-African jurisdictions, they are systemically rejected by the AU and in its wake by the majority of its member states who object to cooperation with the ICC. Thus, the warrants of arrest for war crimes and crimes against humanity (March 4, 2009), then for genocide (July 12, 2010) issued against the Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, following the decision of the Security Council (Resolution 1593 (2005) remanding the situation to Darfur, were not carried out by the authorities of various countries to which he had paid an official visit – Ethiopia, Chad, Kenya, Malawi, Libya, Djibouti, Egypt, Zimbabwe – without being worried. In hopes of delivering him to justice, the AU has otherwise prohibited its members from cooperating with the ICC. To justify its refusal to arrest the Sudanese President, Chad has invoked the ICC’s decision and has explained that it was forced to give precedence to its obligations to the AU over those which resulted from an arrest warrant under the Security Council’s jurisdiction. As for Malawi, it has issued its own warrant by invoking an exiting conflict between the immunity that chiefs of State held on customary international law (CIJ, February 14, 2002, Arrest warrant from April 11, 2000 (Democratic Republic of Congo/Belgium)) and the request of the ICC (founded on article 98-1 of its statute) to arrest and turn over to the Court a head of state currently in office. The same hostility can otherwise be observed in the case of the arrest warrants delivered against M. Gadhafi, June 27, 2011, and certain members of his inner circle, for crimes against humanity (murders and persecutions that were allegedly committed in Libya), under the jurisdiction of the ICC by the Security Council on February 26, 2011. (Resolution 1970 (2011)). However, this did not lead to conflict, due to the death of the Libyan leader.

On the other hand, the situation is completely different for the claims of jurisdiction made on the initiative of authorities of the states concerned – RDC (Situation in the region of Ituri in 2004), Uganda (referral in 2003 on the situation concerning the Lord’s Resistance Army, in the North of the country), the Central African Republic (Crimes committed after 2002), Ivory Coast (post-election violence in 2010-2011), to whom the AU has not shown any particular hostility in any matter. In a well-understood logic of interest, the states involved are, on the contrary, cooperating with the Court throughout each stage of the proceedings. In the Kenyan case, where the accused were reconciled and hold power together, the absence of a clear winner and the alleged abuse by both camps makes cooperation with the ICC, which ultimately imposed its own jurisdiction, contentious. This explains the use of the old argument of National Interest destined to escape from justice. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that they be strong enough to guarantee the immunity of former times for those that would claim it.

References

Mouangue Kobila James, « L’Afrique et les juridictions internationales pénales », Cahier Thycide, (10), February 2012.

Laroche Josepha, (Éd.), Passage au crible, l’actualité internationale 2009-2010, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2010, pp.49-53.

Bussy Florence, Poirmeur Yves, La Justice politique en mutation, LGDJ, 2010.

Oct 22, 2013 | Articles, Fil d'Ariane, Publications (English)

Par Daniel Drache

Acting Director Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies and Professor of Political Science York University

Comments Welcome drache@yorku.ca

www.yorku.ca/drache for other reports and studies

Extrait

The best that can be said about the Sutherland 2004 and the Warwick 2007 Reports on the future of the WTO and the reform of the multilateral trading system is that both boards of enquiry launched modest trial balloons about modifying voting procedures to reinforce the logic of the system. With their ambiguity, blandness, and shortcomings, these high-level bodies did not address the imbalance between the formal legalism of the WTO’s rules and its rule-bending institutional practices. Nor did they propose an acceptable common ground for reform, one that would bridge the deep divisions between members and the G20/G33 coalitions. Most importantly, no candid answer was forthcoming to the question, would a culture of adaptive incrementalism give the WTO new authority to respond to the many challenges the world trading order faced? As such, neither Report was insightful on what Pauwelyn describes as “the delicate balance between law and politics” and the need for alternative forms of global governance and a more effective institutional architecture. A critical reading of both Reports helps shed light on the reasons why the WTO has been unable to move forward and renew itself.

Télécharger l’article The Structural Imbalances of the WTO Reconsidered. A Critical Reading of the Sutherland and Warwick Commissions.

Oct 21, 2013 | Research dissemination, Théorie En Marche

The author, a recognized migration specialist for many years, points out in this booklet a paradox: while the goods, capital and information travels freely, yet, individuals do not all have the right to the international mobility. That is to say, that this very issue discussed here concerns all countries, especially the European states. Indeed, some of them are now experiencing a rise of xenophobia and nationalism that often triumph in the polls. In front of this situation, Catherine Withol de Wenden declares the need to establish an international right of migrants as an urgency and “an essential aspect of human development”. For this political scientist, this would of course mean that we initially define a “soil less and de-territorialized citizenship” to protect them who were about 240 million in 2013 making only 3.1 % of the world population.

Catherine Wihtol de Wenden, Le Droit d’émigrer, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2013, 58 p., bibliography.

Oct 15, 2013 | Nobel Peace Prize, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English), Security

By Josepha Laroche

Translation: Frédéric Ocrisse-Aka

Passage au crible n°93

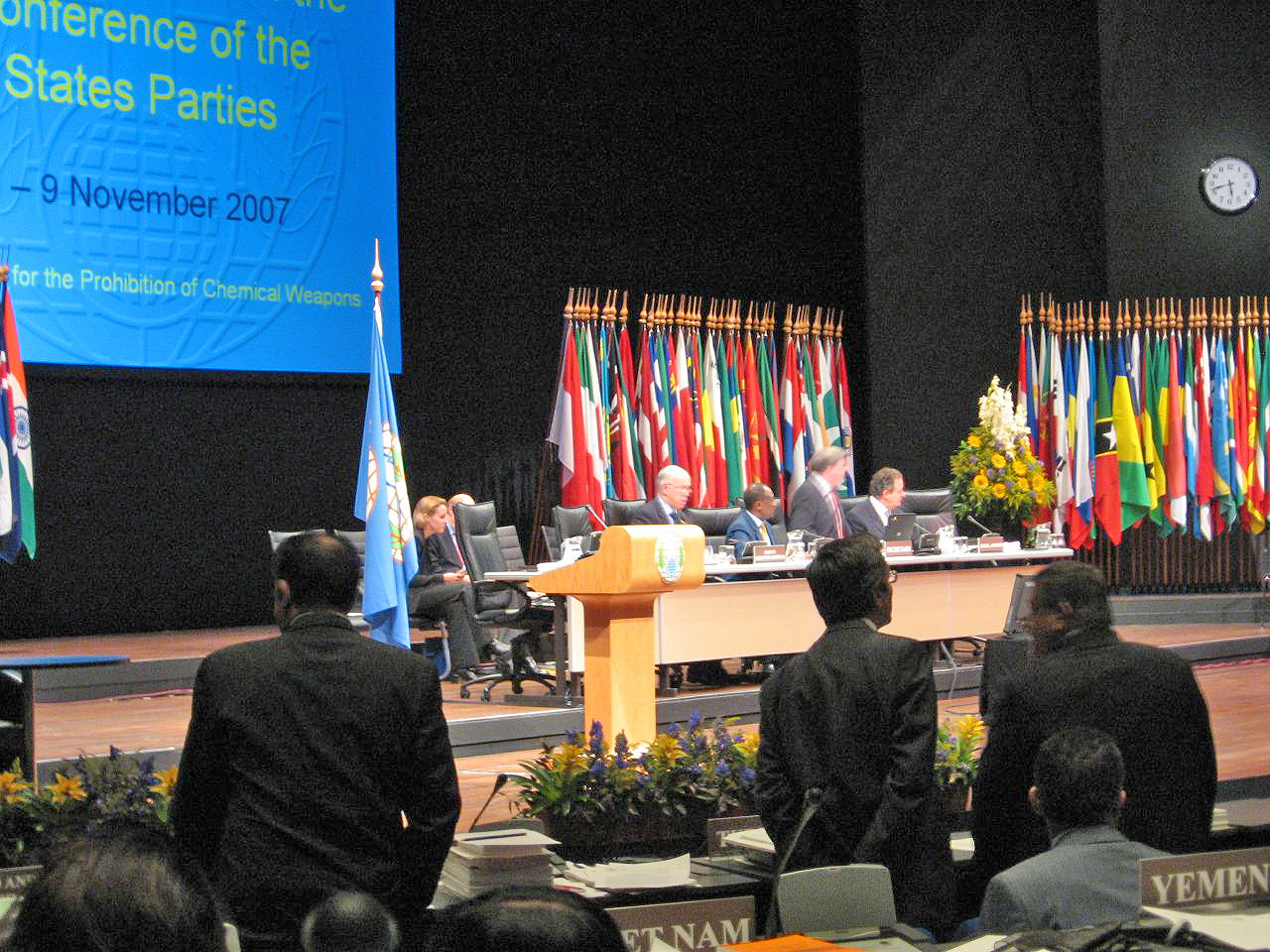

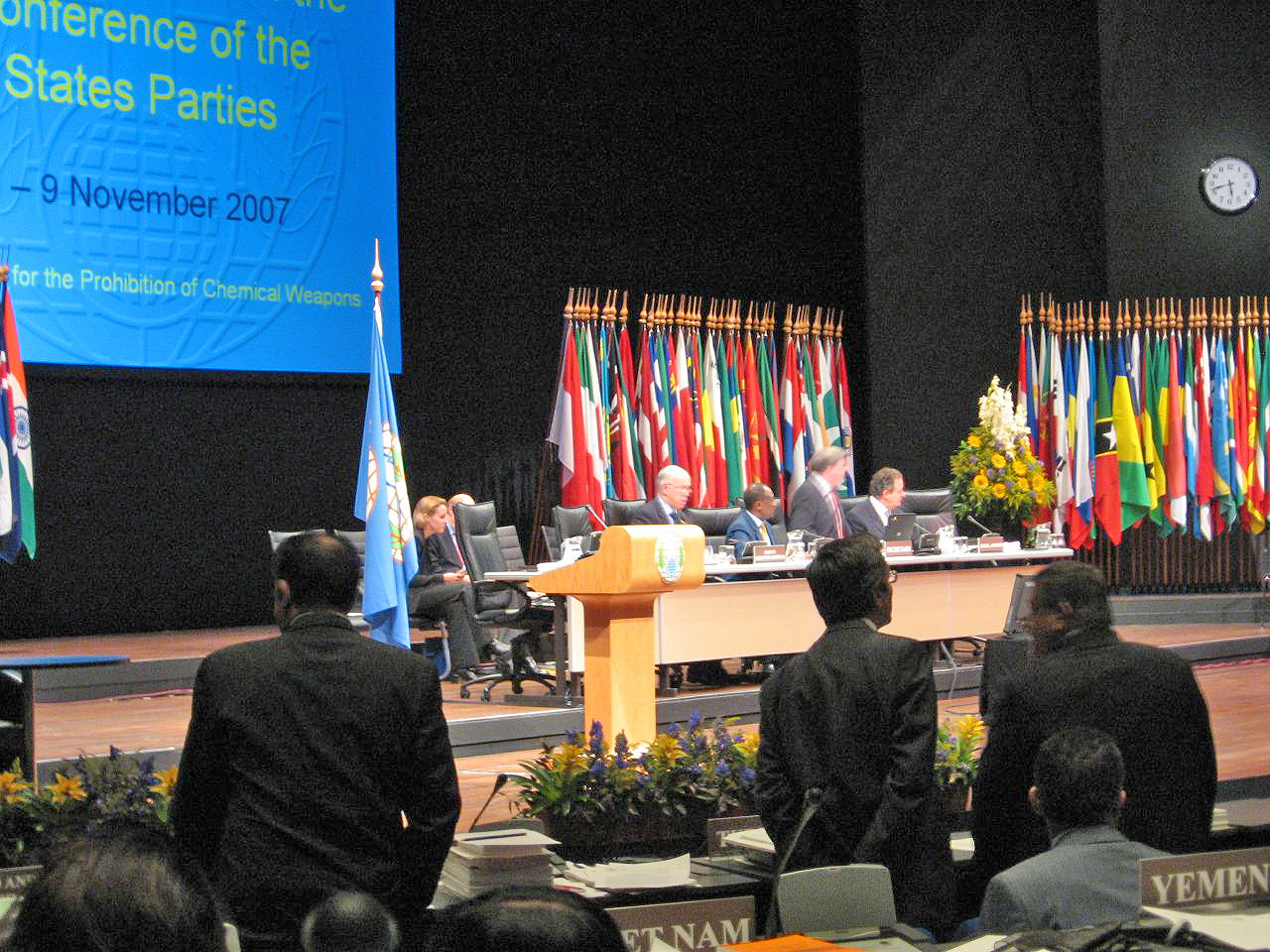

Source : Wikipedia

Source : Wikipedia

While for several weeks, all international media were expecting the young Pakistani activist Malala Yousufzai to be the next recipient, it is finally the OPCW that received on Friday October 11th the 2013 Nobel Peace Prize. Though, contrary to reckless statements by numbers of commentators, there is no reason to be surprised by this reward and even less to denounce an alleged drift from its mission. Instead, prizing this organization with the Nobel emphasizes once more time the consistency of the Nobel diplomacy.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

The OPCW went effective on April 29th, 1997 to ensure compliance with the Convention on the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, signed in 1993. Since then, its mission is to prevent the production and stockpiling of chemical weapons. It has also to verify the destruction of existing stockpiles for the states that have pledged to eliminate them, and it has to ensure that the destruction will be effectively irreversible.

Headquartered in The Hague, it now has 189 member states representing about 98 % of the world population. North Korea, Egypt, Angola and South Sudan have not signed the forbidding treaty, while Burma and Israel, on their own, signed but did not ratify. Syria, on its side, has joined the organization in September only. Since then, the country has submitted an inventory of its chemical arsenal to the international organization which has already started its mission on the Syrian territory. This is to say that the recent Nobel Peace prize currently plays a key role in the dismantling of the chemical weapons held by Syria and therefore in the ongoing conflict.

Despite often being at the heart of conflicts, the OPCW actions have remained very lightly covered. Yet, it has already intervened in many battlefields. So, since 1997, this multilateral body has conducted 286 inspection missions to 86 member states of the Convention, including 2,731 inspections related to the presence of chemical weapons. For instance, its inspectors have destroyed on several fields over 58,000 tons of chemical agents: whether in Iraq, Libya, Russia or the United States. For information, Albania and India have completely destroyed their declared chemical weapons stocks since they are part to the agreement.

For the first time in the history of multilateral disarmament, we are dealing with an institution that works well and managed to put in place highly innovative international disarmament mechanisms. Indeed, the inspectors check on site, and often at short notice, the reality of the commitment of the States, whereas during the Cold War, many treaties were signed in this area without ever being effective.

Theoretical framework

1 . The transfer of a worldwide reputation. Before intervening in the Syrian issue, especially after the 21 August 2013 chemical attack near Damascus, the OPCW was totally unknown to the general public. Yet it has been working for many years on key missions. By awarding the Peace Prize, the Nobel institution chooses to transfer the credit that it owns. It is transferring to the OPCW its worldwide notoriety that has been tied for more than a century to its international awarding system. In doing so, the Nobel Institution offers to the OPCW actions a media attention that this technical body was missing so far.

2 . The legitimacy of a diplomatic interference. Many believe that this award finally endorses Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the manipulation of the OPCW by Moscow. On our side, we will especially emphasize the Oslo Committee will, to come by high-jacking alongside the States to participate in their High Politics. In this case, he burst onto the world stage by interfering with the settlement of the Syrian conflict. By choosing to pay a tribute to collective security and multilateralism, not only it puts these concepts on the international agenda, but also it sets itself – through this symbolic power grab – as the mandatory point of contact for States, and conflict stakeholders. This way, the Nobel is able to counter this diplomatic intrusion with the entire legitimacy it has built for over a century.

Analysis

For sure, it is disappointing that the young Pakistani Malala Yousafzai was not rewarded. Indeed she symbolized women’s fight against the Taliban and the fight for the right of all to education. It is equally unfortunate that Dr. Denis Mukwege, who struggles to help women victims of rape in the DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo), was not awarded a Nobel. The Congolese gynecologist dubbed “the man who repairs the women” has for nearly 15 years treated 40,000 women victims of rape or sexual violence in eastern Congo. Already fit for a Nobel last year, he had just narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in October 2012. However, there is no reason to think that these two individuals will not win this award in the future, as their profile matches the requirements of Alfred Nobel will written on November 27, 1895,and they correspond to the Nobel doxa. Yet, the Nobel Peace Prize should not however be analyzed in terms of any given moral or meritocratic criteria. There is no mistake, it is politics and it has always been about politics. More specifically, a diplomatic line repeated and strengthened prize after prize. Besides, it is how Alfred Nobel himself was conceiving it. Therefore there is no doctrinal drift in opposition to several allegations by number of comments entirely wrong.

In fact, since the Nobel jury’s choice fell on President Obama, this is less of a reward for a completed work. This is not new, this orientation has always existed. But year after year there is a confirmation that this global distinction currently serves preferably a grand ambition: to rule the world by influencing a course, by always trying to influence the direction of global issues on the political agenda. By seizing a window of opportunity, the institution sensationally burst onto the world stage – if we are to believe the bunch of criticism that goes with it – to interfere with the main current issues with full legitimacy. Isn’t it a promoter of universal values that no one would deny? It intends to use its notoriety to promote its own priorities and values, where states have shown their powerlessness so far. However, this diplomacy as innovative as interventionist, based on an interference principle is not without risks for the Nobel Committee.

By investing in an ongoing process, the institution gives a mission-order to the winner; it gives him credit and mandate to effectively complete the project which is carries.

However, if it is an obligation of result and therefore a burden for the winner, it is even a more risky bet for the Committee as it involves betting on the long-term its credibility.

References

Laroche Josepha, Les Prix Nobel, sociologie d’une élite transnationale, Montréal, Liber, 2012.

Laroche Josepha, (Éd.), Passage au crible, l’actualité internationale 2009-2010, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2010, pp. 19-22 ; pp. 41-45.

Laroche Josepha, (Éd.), Passage au crible, l’actualité internationale 2011, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2012, pp. 47-52.

Oct 5, 2013 | Human rights, Passage au crible (English)

By Michaël Cousin

Translation: Lawrence Myers

Passage au crible n°92

Pixabay

On June 30, 2013, Vladimir Putin announced a law against “propaganda encouraging minors to accept non traditional sexual relationships”. This law aims to prevent LGBTI activists (Lesbian, Gay, Bi, Transgender and Intersex) from using public space for promoting their rights, and also forbids, “the diffusion of all information likely to arouse this type of interest in minors”. However, the effect of this new legislation is the endangering of liberty of expression and, de facto, liberty of the press. It otherwise not only sanctions Russian citizens, but also extends to foreigners present on Russian soil.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

On September 27, 2012, the United Nations Human Rights Council voted a resolution by majority, initiated by Russia, for the “Promotion of Human Rights and Fundamental Liberties for a Better Understanding of the Traditional Values of Humanity: Best Practices”. This text thus reveals the profound aversion that Moscow has developed against the LGBTI community and has led to the rejection in December 2008 of the “Declaration Relative to Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.”

Still, during a vote on this new provision, the Council charged the Advisory Committee to pursue its study on the role of traditional values. The report’s conclusions were made public last March. In it, the UN proceedings very clearly warn against resorting to “traditional values,” notably when States seek to systematize or to discriminate against a part of their population. But, three months later, this warning was unable to prevent the Duma from voting a new legislative text obviously targeting homosexuals and bisexuals who are labeled “non traditional,” therefore neglecting Human Rights at the same time.

In this regard, multiple actors have intervened in order to exert pressure on Moscow by asking the IOC (International Olympic Committee) to respect and to make others respect its Charter, which contains several articles protecting sexual orientation and freedom of expression. Nonetheless, the Committee confirmed last September that it would not deprive Russia from organizing the upcoming Olympics – to be held February 7-23, 2014, in Sochi – and this despite the Russian government’s persistence to seek to apply its liberty-killing clauses before, during, and after the Games.

Moreover, Russia has also been chosen to organize the 2018 FIFA World Cup. Consequently, it will have to comply with the code set forth by article 3 of FIFA’s (International Federation of Association Football) code. Said article protects the sexual orientation of participants. In the case at hand, the association asked the Russian government to clarify its law. In parallel, other western initiatives are also taking shape aiming to block the Russian law. Take for example the Russian vodka boycott put into place by gay bars and nightclubs or the creation of a Facebook page campaigning for a Sochi Olympic Games boycott. In the face of these mobilizations, the Russian minister of sports, Vitali Moutko, was provoked to declare in August 2013 that, “The stronger that Russia becomes, the more she displeases certain individuals. We are simply a unique country”. Even so, this remark implicitly creates an amalgam of the country’s economic system and the organization of its civil society, notably as it pertains to each person’s sexual orientation. As it happens, the Putin-era homophobia is a prolongation of the attitude already crushing the country under Stalin whose regime defined homosexuality as an illness inherent to the bourgeoisie and to capitalism.

Theoretical framework

The ahistorical construction and mystification of traditional values. The rights, which were historically constructed as universal henceforth, include all human communities, no matter their culture. This very principal of standardization often finds itself often poorly perceived by populations. The aforementioned feel all the more threatened in their new social representations as new international norms are imposed on them. It is in light of this feeling of loss of a point of reference that social forces are established in order to reinvent and glorify the supposed traditional values. From there, these antiestablishment movements present themselves as spokespersons of traditional populations that have allegedly been, they say, stripped of their identity. In doing so, in order to legitimize their stance, they rely on a mythology of origins, a supposed panacea to economic, social, and cultural problems, brought about by the process of globalization.

The disparity of transnational mobilizations. Transnational protests emanate not only from numerous organizations, but also, sometimes from networked individuals. Yet, if this leverage by intervening individuals sometimes reinforces collective action, it more often leads to divergent discourses and frequently ends in tension or conflict. The transnational movement thus finds itself all the more weakened.

Analysis

While Russia definitively decriminalized homosexuality in 1993, homosexuals are today first and foremost considered to be Russian before being recognized as homosexual. In reality, since the globalization of the fight against homophobia has rapidly expanded and since the promotion of the “Declaration Relative to Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity,” Russia has chosen – as have many other countries – to maintain its current homophobic leanings. In so doing, the already unstable situation of homosexual persons has not ceased to deteriorate.

Beyond any doubt, these repressive policies put into effect by the established authority weigh on the values and preferences of citizens. For the Russian government, it is a question of finding a way to avoid any debate on economic and social problems by designating a scapegoat associated with demonized globalization. We shall in this case establish a parallel with certain African nations such as Uganda, a country where homosexual persons are allegedly “Caucasians” from whom one must protect oneself.

Finally, in light of these punitive provisions, we cannot help but be reminded that Stalin sent thousands of homosexuals to the gulag.

From now on, with this new law neither newspapers nor activist associations will be able to mention the existence of sexual minorities. However, the civil society is already proving to be considerably weakened by the autocratic power in place in such a way that the associations defending homosexual groups will have little weight in the face of the established order. This is especially true, as the links between these local and transnational entities remain fragile. No coordination has been set up between the boycotts and the pressure on the decisions of the IOC or FIFA. In the same way, the petitions and international “kiss-ins” are not integrated into a logic of global protest. It follows that the transnational movement is becoming fatigued, which explains why the IOC consequently decided to organize the winter Olympics in Sochi, as it had initially planned; the only missing piece is FIFA’s decision.

References

“ Droits des LGBT et droits humains en Russie : l’inter-LGBT interpelle le Président de la République Française et appelle à participer au rassemblement du 13 Septembre sur le Parvis des Droits de l’Homme”, Inter-LGBT, 04/09/2013, http://www.inter-lgbt.org/spip/php?article2013

Laroche Josepha, Politique Internationale, 2e éd., Paris, LGDJ., 2000.

Siméant Johanna, “ La transnationalisation de l’action collective”, in : Agrikoliansky Éric, Sommier Isabelle, Fillieule Oliver (Éds.), Penser les mouvements sociaux, Paris, La Découverte, 2010, pp.121-144.