Mar 7, 2017 | Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English)

By Josepha Laroche

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n° 152

Source: Flickr – Xavier Badosa

Source: Flickr – Xavier Badosa

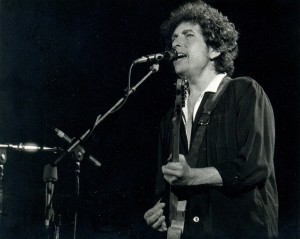

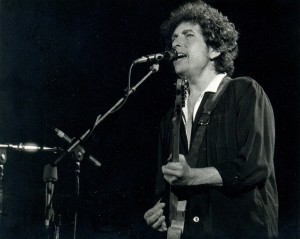

In a surprise move, on October 13, 2016, the Swedish Academy awarded the Nobel Literature Prize to the musician and poet Bob Dylan, « for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition ».

The American singer is the successor of Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievitch, first Russian speaking woman to receive this award. However, he said he would not attend the December 10th prize ceremony in Stockholm, held under the patronage of King of Sweden Carl XVI Gustaf.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

On his quest for a distinctive mechanism to pacify the global scene, Swedish industrial chemist and philanthropist Alfred Nobel created through his will, on November 27th 1895, five annual prizes: physics, chemistry, physiology-medicine, literature and a peace prize. He laid the foundations of a purposefully pacifist and cosmopolitan international system of rewards. He also detailed that the peace prize would only be awarded by the Norwegian Parliament (Storting) and handed in Oslo. At the time, this was received with strong disapproval from Sweden as Norway was still under Stockholm’s authority. After Nobel’s death on 1896, many years passed before the first prizes were awarded. Indeed, the disinherited Nobel family engaged in lengthy court proceedings with the testamentary executors of the magnate. Only in 1901 were bestowed the first distinctions.

With regard to the literature prize, the institution issued over decades many normative preferences that progressively became authoritative on the global scene. Since the beginning, the Nobel jury strived to attain two complementary objectives. It honoured famous writers, but also fostered innovation and favoured unnoticed authors. For instance, the Nobel literature jury, driven by Lars Gyllensten, privileged innovative reality depiction through writing. He then declared « the prize should not crown the merits of the past […] it should not be a mere decoration […] but also constitute a bet on the future […] in order for the laureate to create a piece that would still deserve encouragement ». The Nobel institution looked up to « enable an original, innovative writer to pursue his or her work; allow a literary genre, unnoticed but prolific, to emerge and receive help; promote a neglected cultural or linguistic area, or other initiatives and human struggles with an award ». This is why the Committee undertook the role of discoverer, to distinguish overlooked works and genres, and favour writers with no international readership.

This explains the decisions of Swedish academicians that might have sometimes appeared as puzzling. This was the case in 1977, as Spanish poet Vicente Aleixandre had only published once, in France, when he received the Nobel. As he was hastily demoted to the status of « obscure writer », by some journalists, Swedish Academy Secretary Lars Gyllensten backed the choice of the jury stating that the « he attribution of the Nobel prize of literature did not recompense the best writer of the time, as this was an impossible task. » This consideration is still quite relevant today and has made related debates pointless. In 1979, poetry composition was again distinguished and Greek esoteric poet Odysseas Elytis received a Nobel. In 1987, the Academy confirmed its line and honoured the young leader of Russian poetry Joseph Brodsky, followed by Irish poet Seamus Heaney in 1995, and Polish poetess Wislawa Szymborska in 1996. Poetry, deemed to be unaccessible to the wider audience appears as a priority. In fact, when the Nobel jury recognises Bob Dylan in 2016 as an inventor of « new poetic expressions », it only replicates the doctrine drawn out year after year, a doctrine faithful to Alfred Nobel’s preferences, a great poetry enthusiast.

Theoretical framework

1. A maker of the norm. With a distinctive and sometimes unknown masterpiece selection, the Nobel literature committee sets out priorities and aims to shape the mainstream trend. By doing so, it strives to promote overlooked literary genres with a small audience. For this reason, the committee became prevalent in defining literary and aesthetic norms over the last decades.

2. A universal prescriber. By recognising a world famous life’s work and also new forms of expression as legitimate, it intervenes as a global prescribing authority.

Analysis

Contrary to the long tradition of reservation and secrecy characteristic to the institution, General Secretary to the Nobel Committee for literature Sara Danius highlighted that her peers showed «consistency » while voting in favour of American singer Bob Dylan. She indirectly replied to the many critics aroused when the name of the laureate was unveiled. « He continues a tradition that goes back to William Blake », the famous English poet who died in 1827, she added.

The problem put forward by her detractors is linked to the fact that the grantee was mainly known as a singer, and not as a writer. The symbolic maneuver of the Nobel jury lies in integrating the American artist in the heart of a literary genre that has always been supported by the institution: poetry. From then, the nobelisation appears to follow a, somehow, traditional orientation. The infringement is then to give new boundaries to the poetic form. But discovering and consecrating « new poetic expressions » implies necessarily to broaden the scope and innovate through new vectors of poetry. Bob Dylan’s work, interwoven with rock, folk, country, soul, blues and popular tunes, makes him a syncretic and innovative songwriter. In granting him a Nobel Prize in literature, the institution seeks not to promote an already widely acclaimed artist, or make famous a celebrity. But it certainly seeks to legitimise and define, on the global scene, writing standards that have been encased until now in songwriting and music. This genre, mainly perceived as popular and marginal, is now reconsidered and honoured by the Nobel prize. Beyond Bob Dylan, the individual, the committee states its determination to capture, recognise and promote new literary forms. In other words, this nobelisation follows an historical continuum that has never been challenged since 1901. It allows one to delineate, in the light infringement committed today, tomorrow’s conformism, as the Nobel diplomacy’s normative power imposes and globalises new modes of expression previously considered as secondary.

References

Brierre Jean-Dominique, Bob Dylan, poète de sa vie, Paris, Archipel, 2016.

Dylan Bob, Cott Jonathan, Dylan par Dylan: Interviews 1962-2004, Paris, Bartillat, 2007.

Laroche Josepha, Les Prix Nobel. Sociologie d’une élite transnationale, Montréal, Liber, 2012, 184 p.

Feb 28, 2017 | Climate change, Diplomacy, environment, Passage au crible (English)

By Simon Uzenat

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n° 151

Chaos International

Chaos International

The 22nd CoP (Conference of the Parties) to the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) was held in Marrakesh from November 7 to 19, 2016. More than 22000 participants gathered – 40% less than for the Paris Conference – with nearly 16000 governmental representatives, more than 5000 representatives of UN organisations, IGOs (Intergovernmental organisations) and NGOs (-50%), and 1200 media representatives (-66%). This technical conference was tasked with putting forward an implementation strategy for the 21st CoP diplomatic turning point, later formalised in the Paris Agreement. The agreement came into force on November 4, 2016, thirty days after its ratification by 55 countries, representing 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions. The 22nd CoP was also the first session of the CMA (Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement).

This international conference has also been impacted by the election of Republican candidate Donald Trump, a well-known climate sceptic, to the presidency of the United States on November 8, 2016. The President-elected clearly stated his intention to opt out from the Paris Agreement. This political event engendered even more uncertainty with regard to the achievement, within reasonable timeframes of the practical objectives (attenuation, financing, technology transfers) pivotal to climate resilience.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Since the beginning, climate negotiations have been paced by key diplomatic events with mixed results (Kyoto, Copenhagen, Paris), and operational conferences aiming to finalise and detail the implementation of major agreements. The 22nd CoP is consistent with a multilateral session held fifteen years earlier, when Morocco first welcomed climate negotiators. From October 29 to November 9, 2001, the representatives of the 7th CoP gathered in Marrakesh to outline an implementation plan for the Kyoto Protocol, signed in 1997, and establish a juridical interpretation of the Buenos Aires Action Plan adopted in 1998, in the context of the Marrakesh Agreements. The election of Georges W. Bush, firmly opposed to any binding approach that would exclude China and developing States, raised serious concerns, especially when he confirmed his choice, in 2001, to not submit the protocol to the Senate for ratification. Combined with other tensions, mainly related to the scale and deadlines of the emission reductions, framed for developed countries in the Annex1 of the Protocol, the American unilateralism delayed the inception date of the Kyoto Protocol until February 16, 2005.

Prior to the 22nd CoP, several international decisions have maintained the Paris Agreement momentum. The resolution voted on October 6, 2016 by the ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organisation) first established a global mechanism of compensation for civil aviation emissions. The following Kigali amendment, adopted on October 15, 2016 after seven years of negotiations in the framework of the Montreal Protocol approved progressive elimination of hydrofluorocarbons (HFC) known to create a greenhouse effect 14000 times more powerful than CO2.

Theoretical framework

1. A fragmented multilateralism. The climate arena is strategically divided between the several dimensions of the international negotiations (conferences, work groups, partnerships, plans, programs, funds). The multiplication of these platforms follows the growing complexity of global issues (science, technology, finance) and a diversification of the levels of action (local to global). But these platforms also frame potential tensions by identifying the most relevant common thread of deeply heterogenous and competitive players. But as the Copenhagen coercive approach comes to an end, this atomisation might also reduce the operational scope of the climate deal.

2. A new schedule for climate action. Based on incentives, good will and consent, the Paris Agreement has set up long-term objectives and renounced any binding time-frame, even though the emergency is widely acknowledged. Several intermediate deadlines have been added (2018, 2020, 2050) with no associated targets or sanctions and varying with the topic (attenuation, adaptation funding). This critically undermines the probability to limit global warming by 2°C before 2100. Until now, nationally determined contributions rather lead to an increase of 3°C.

Analysis

Initiated by the Moroccan presidency and amended by different groups of countries, the Marrakesh Conference has adopted the Action Proclamation for our Climate and Sustainable Development. This declaration of intent merely recalls the principles of the Paris Agreement, and refers to « the urgent duty to respond to climate emergency », together with the inclusive nature of the Agreement in respect of the common but differentiated responsibilities of the States. This declaration, acting as a self-fulfilling prophecy, calls for an « urgent, irreversible, and unstoppable change » as new UNFCCC Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa said. It also factors in all the obstacles on the way to climate resilience: « We call for a wider solidarity with the most vulnerable States, […] we call all non-State actors to join us and mobilise for immediate and ambitious action ». Even if the date has been brought forward by one year, governments have agreed on the 2018 deadline – one year too late for LDCs (Less Developed Countries) – for the operational completion of the Paris Agreement. 2018 will be the year of the 24th CoP and third phase of the first session of the CMA.

The ambiguities of the Paris Agreement have altered the pace and quality of the negotiations, especially without global vision or control over the States commitments. The difficulties associated with implementing debate sessions for this agreement have also delayed the progression of the work: while many representatives disagreed over approaches and calendars, the APA (Ad Hoc Working Group on Paris Agreement) did not reconvene on the second week of the conference. President Trump’s election also emerged in the political leaders’ debates and reunions. The US President may have all the legal rights to opt out of the Paris Agreement before the end of his mandate. But the treaty’s quick entry into of force and international outreach, the strong commitment of China – world’s first emitter of greenhouse gas emissions – and calls from American non-State actors such as Nike and Starbucks or local authorities have made a complete US withdrawal unlikely. As the text’s formal aspect is extremely versatile, the main risk remains US inaction or delaying tactics.

Several simultaneous initiatives have been launched to balance this potential inertia and revive the climate arena. The Marrakesh roadmap for the Climate Summit for Local and Regional Leaders, held on November 14, calls for « reinforced and simplified direct access modalities to dedicated climate funds », and announced the launch of the 2017 global campaign for localising climate finance. This is one of the solution put forward as « financial resources do not match the ambition of the international community ». Many representatives have noted that French and Moroccan climate champions Laurence Tubiana and Hakima El Haité, on the Summit’s closing ceremony, while asking them to devise territorial scenarios for 2050, never referred to any available mid or long terms resources. On November 15, 42 countries signed the NDC Partnership (Nationally Determined Contribution), co-funded by Morocco and Germany. It ambitions to be a collaboration platform for developing and developed countries, with international institutions to stimulate and hasten the implementation of NDCs in various sectors and at all decision levels in developing countries. It offers an online database – created with the UNFCCC, the Moroccan government and the German International Agency for Cooperation – that lists more than 300 bilateral and multilateral funds.

The launch of the Marrakesh Partnership for Global Climate Action by the climate champions, in the presence of 22nd CoP President Salaheddine Mezouar and United Nations Secretary General Mr. Ban Ki-Moon, aims to foster non-State action for the 2017-2020 period. Following the Lima-Paris action plan transformed in Global Climate Action Agenda, this partnership is first meant to boost and promote concrete commitments beyond uncertain State promises. Keeping global warming well below 2 degrees implies to step up efforts before 2020. The financial issue remains prominent: infrastructure investments required to undertake a low carbon economy amount to 4000 billion dollars for the next 15 years. The 100 billion dollar funding per year, that must be mobilised before 2020 by developed States and that have been debated over since Copenhagen are only but a drop in the ocean of climate emergency. The determination to act is so low that the identity of the applicant country for the 23rd CoP has only been unveiled during the Marrakesh conference. It has been decided that the 23rd climate conference would be chaired by the Fidji Islands and be held in Bonn, the UNFCCC’s head office.

Despite many scientific warnings, alarms bells set off by most vulnerable populations and various transnational mobilisations, the current commitments of the States will not grant climate justice. The partial reconfiguration of the climate arena, now involving non-State parties, might alleviate inaction, but only if substantial human and financial resources are deployed.

References

Aykut Stefan C., Dahan Amy, Gouverner le climat ? 20 ans de négociations internationales, Paris, Les Presses de Sciences Po, 2014.

Barrett Scott, Environment and Statecraft: the Strategy of Environmental Treaty-Making, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2003.

Keohane Robert O., Victor David G., « The Regime Complex for Climate Change », Perspectives on Politics, 9 (1), 2011, p. 7-23.

Uzenat Simon, « Une reconfiguration partielle de l’arène climatique. Le 1er Sommet Climate Chance des acteurs non-étatiques, 26-28 septembre 2016 à Nantes », Passage au crible (147), Nov 2, 2016.

Feb 17, 2017 | China, Development, Foreign policy, Globalization, Passage au crible (English), Publications (English)

Par Moustafa Benberrah

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n° 150

Source: Wikimedia

After a four-year construction period, Ethiopia inaugurated a railway line connecting its capital city Addis-Abeba with Djibouti. Built by Chinese companies, this new access to the Red Sea should boost the Ethiopian economy. This 3.4 billion dollar project (3 billion euros) has been financed up to 70% by the Chinese investment bank Exim.

> Historical background

> Theoritical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

The growing development of China’s foreign operations is a clear sign of transformation of its global status. Responding to President Hu Jintao’s « going out » appeal (zouchuqu), China explored new markets and supply resources worldwide. Simultaneously, the country has been looking for new allies. This offensive has spread over areas traditionally marked by a Western presence. In this line, Beijing has continuously developed its influence over the African continent and has organised China-Africa summits based on multilateralism. This strategy has contributed to enhance and comfort its international stature.

The exchanges between the DRC (Democratic Republic of China) and Africa reached 200 billion dollars in 2015, against 12,39 billion dollars in 2002. In May 2014, Chinese Prime Minister Li Kegiang declared his intentions of doubling these results by 2020. Today, the DRC has clearly established itself as the first commercial partner for many African countries. More than 2500 Chinese companies, covering a wide variety of sectors from hydrocarbons to construction industry are now working with Africa. Indeed, the construction sector is a unique opportunity for companies to showcase their knowledge and professionalism. Moreover, this type of investment matches the official line highlighting the need to support a continent first and foremost considered as a fully-fledged partner and not only as a market.

China’s financial presence relies essentially on service delivery and FDI (Foreign Direct Investments), two major strengths which enabled the country to become one of the most prominent foreign investors. However, this assessment has to be proportionate to China’s global investments, as in Africa they only amount to 0,2% of its total FDI. The construction sector embodies this reality, as Chinese companies do not become either infrastructure owners or shareholders. Yet, the definition of FDI as established by international organisations imply that « investors » are companies that possess at least « 10% or more in actions or votes within a company ». As a consequence, China’s presence in Africa is now assuming more indirect forms, which are very typical of the ongoing globalisation process.

Theoritical background

1. A pragmatic enterprise. For Johnson Chalmers, this type of orientation illustrates how a powerful State leads industrial policies and steers production while encouraging strong managerial autonomy. In other terms, this configuration puts more emphasis on increasing market shares than short-term profits.

2. The rise of a developmental State. The Chinese State asserts his position as a central player of the international cooperation. It exercises its prerogatives as public power either directly, or through chosen intermediaries. However, some players remain beyond its control and may contest its authority.

Analysis

For a long time, the Democratic Republic of China has not used the word « aid », and would rather refer to a « win-win partnership » or « mutual assistance » between countries from the Global South. It was not until the publication of the White Paper on Foreign Aid in April 2011, that the government actually adopted this terminology. This paper imposes a buy-back process together with a set of general contracts to countries recipient of the aid. As a consequence, these provisions require compulsory use of firms and workers rather than payments in raw materials. This « Angolan model » applies to Central African countries rather than to South African and Northern African countries, which enjoy more negotiation power. But eventually, this type of public development aid has become a tool of Chinese diplomacy and an integral part of its soft power.

Chinese authorities have developed two types of mechanisms: they first allocate donations and interest-free loans with associated technical assistance. They also write off debts, which represents up to 70% of the aid. Secondly, they offer loans at preferential interest rates targeted at industrial projects and infrastructures. These loans are imperatively reimbursed on a floating rate and over modifiable duration, and average around 2% over 10 to 15 years. This new requirement has been added in 1995 with the creation of the China Ex-Im Bank. Placed under the control of MOFCOM (Ministry of Commerce) and the Foreign Office, this bank benefits from 3500 billion euros of Chinese currency reserve (a third of the planet’s liquidities) and embodies the financial arm of China’s foreign policy. It should be underlined that this institution is strengthened by four distinct organisations currently leading the aid policy: the MOFCOM, the Foreign Office, the CAD Fund (China-Africa Development Fund) and the SINOSURE (China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation). Moreover, these entities receive support from local governments, that play a pivotal role within the management of this process.

But this strategy is not overseen by any central organisation able to coordinate these actors. Yet, recurrent discrepancies have appeared between public and private interests. Indeed, these organisations form the pillars of a developmental State compelled to take all necessary measures to achieve its goal. In this regard, collaboration with major private actors is mandatory, to such extent that they influence the whole State’s policy.

China’s presence on the global scene has spurred competition between big national and international groups. To developing countries, the DRC stands now as a balance to the political and ideological influence of Western States. But the very attractiveness of the Chinese model should be examined, as China’s control policy contributes to increasing the debt of several nations such as Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Ghana. Moreover, the massive use of Chinese workforce together with uncontrolled immigration has fuelled criticism in these regions already burdened with high unemployment rates. Furthermore, Chinese products’ quality and infrastructures are widely questioned. Finally, Chinese companies are repeatedly involved in many corruption scandals. Mainly active within the construction sector, these companies have altered the image of Chinese power and distorted the message destined to developing countries. China is thus compelled to fine-tune its strategy to the complex constraints of a fragmented and instable Africa

.

References

Benberrah Moustafa, « L’asymétrie sociopolitique d’une coopération économique. L’implantation dominatrice des firmes chinoises en Algérie », Passage au crible, (127), 29 mai 2015. Disponible sur : http://urlz.fr/3wcs

Cabestan Jean Pierre, « La Chine et l’Éthiopie : entre affinités autoritaires et coopération économique », Perspectives chinoises, (4), 2012, pp. 57-68.

Chalmers Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy 1925-1975, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1982.

Gabas Jean-Jacques, Chaponnière Jean-Raphaël (Éds), Le Temps de la Chine en Afrique, Paris, Karthala, , 2012.

OCDE, « Perspectives économiques de l’OCDE », OCDE, (73), 2003.

Pairault Thierry, Talahite Fatiha (Éds), Chine-Algérie, une relation singulière en Afrique, Paris, Riveneuve éditions, 2014.

Feb 17, 2017 | Global Public Goods, Global Public Health, Humanitarian, Non-state diplomacy, Passage au crible (English), Publications (English)

By Clément Paule

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n° 149

Source: Source: Wikipedia

Source: Source: Wikipedia

Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 US Presidential elections marks the end of a particularly fierce and conflictual electoral campaign. As a matter of fact, the campaign of its rival Hillary Clinton has been stained with various controversies, such as the email affair – related to the use of a private mailbox server when she led the US State Department. Fuelled by computer hacks targeting the DNC (Democratic National Committee) and relatives of the Democratic candidate, the WikiLeaks website published several thousand files during summer 2016. These leaks sustained the controversy on the Clinton Foundation – which became, in 2013, the Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton Foundation – and was criticised by Republican detractors for its fundraising techniques. But these issues had been expressed as soon as 2008, when Hillary Clinton was about to step up as secretary of State in the Obama administration. In spite of signing a Memorandum of Understanding to prevent any conflicts of interest, the ex–Senator of New York evolved within an unprecedented power configuration. In these conditions, the Foundation has been summoned in various proceedings and is also said to be under investigation from the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) according to the Wall Street Journal.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

Legally established in 1997 to manage the building of a museum in Arkansas, this philanthropic organisation is closely related to the post-presidential career of Bill Clinton. In January 2001, he stepped out from his second mandate at the White House, tainted with the Lewinsky scandal. Since then, the former head of State tried to clear his name through intense public activity. While supporting his wife career, Bill Clinton has been involved in the humanitarian response to Aceh – destroyed after the tsunami of December 26, 2004 – and also in the rebuilding of New-Orleans after Hurricane Katrina struck. These multiple commitments have been supported by the continuous mobilisation of faithful young collaborators such as Laura Graham or Douglas Band, and well-established advisors, of which Bruce Lindsey or Ira Magaziner. They led the development of the Clinton Foundation which quickly became a world-renowned brand.

The institution won its credentials with the launch of the CGI (Clinton Global Initiative) in September 2005. Each year, this flagship project reunites several international leaders – national Heads of State, artists and businessmen – on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly. Very popular amongst the media, this meeting – with a quite expensive admission fee – consolidates a powerful network of donators. This network includes governments – from Saudi Arabia to Norway – but also billionaires – such as Carlos Slim, Rupert Murdoch or Denis O’Brien – and Hollywood stars. CGI members are invited to commit to innovative projects from social engineering to mercantile rationality. The sudden development of the Clinton Foundation can be measured in terms of human resources – more than two thousand employees in thirty countries in 2016 – and also in financial terms. A recent inquiry from the Washington Post revealed than more than 2 billion dollars were received as donations between 2001 and 2015, from which only 262 millions for the sole year 2013.

.

Theoretical framework

1. A philanthropic coalition built on the Clintons’ political capital. The Foundation acts as an intermediary – a broker – between various worlds: the international business community, UN bodies, the diplomatic arena, the show-business industry and the non-profit sector. In this line, it supports lucrative, charitable projects with significant media potential, while the Clintons’ reputation benefits from their expected success.

2. The opacity of a structural overlapping. The differentiation of positions – and mainly, the distinction between public and private – appears to fade within this system of contributors exchanging physical and symbolic goods. This ambivalence, maintained on every level, raised suspicions while Hillary Clinton unveiled her presidential ambitions.

Analysis

The Clinton Foundation has been active in the United States and around the world, on a wide variety of topics including public health, women’s rights and climate change. This vast mission has been declined through a myriad of autonomous programs, such as the CHAI (Clinton Health Access Initiative). The organisation has adopted the smart power doctrine, as promoted by Hillary Clinton in the Senate, and advocates an approach based on innovation, flexibility and outcomes. Contrary to traditional methods, the Foundation seldom funds other actors and leaves aside operational activities, focusing on upstream negotiations to foster partnerships, specifically with transnational firms. To such extent that an article of the New York Times has described the Foundation as a global non-profit consultancy exploring new markets in the Global South for the interest of its donators. The sharp price decline of several medical treatments stands among one of its indisputable successes – such as antiretrovirals in Rwanda – obtained through agreements ensuring steady joint orders to pharmaceutical laboratories. However, these methods have also failed, as exemplified through the efforts put in Haiti and especially in the industrial park of Caracol, after the earthquake of January 12, 2010.

Beyond this mixed picture, the philanthropic entity raised even more concerns when Hillary Clinton led the United States foreign policy between 2009 and 2013. Numerous pundits pinpointed a pay-to-play situation, where special access to the government bypassed traditional channels of institutional lobbying. Some donations would not have been declared, such as a contribution of half a million dollars allocated to the Haiti humanitarian crisis by the Algerian government. Several media have also objected to the commercial operations of one of CGI’s major funders, Canadian billionaire Frank Giustra. Moreover, the Swiss bank UBS would have increased its contributions to the caritative organisation after the settlement of a litigation with the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) under the patronage of Hillary Clinton. On the way to the 2016 Presidential election, these elements have been reported by the Wall Street Journal and ultra-conservative website Breitbart News, also known to have published the damning book Clinton Cash. Notwithstanding the suspicions of self-enrichment – as paid lectures would have represented a profit of several dozen million dollars to the Clinton family – this partisan offensive aims to describe a corrupt system of elites standing at the top level of the Federal State.

Facing these allegations, the Foundation only reaffirmed its political neutrality while some of its champions, such as economist Paul Krugman, stigmatised an unfair ideological bias against public personalities. If no smoking gun has yet been found, internal tensions seem to have maintained a chronic lack of transparency. From 2011, the rise of Chelsea Clinton within the organisation has met opposition from one of the historical partners, Douglas Band. Initiator of the CGI, he has been accused of requesting payment from Bill Clinton and has been said to use this privileged position to develop his own consultancy firm Teneo,. Such methods are widespread within Hillary Clinton’s circles: her relatives, BlackIvy Group creator Cheryl Mills and Huma Abedin have simultaneously occupied positions within the federal administration and the Clinton Foundation. Beyond the extreme polarisation of the electoral campaign, this structural porosity may reveal a complete overhaul of the boundaries of the political field by elites. A philanthropic facade cannot conceal such a power reconfiguration, ultimately sustained by an entanglement of powerful interests.

References

Bishop Matthew, Green Michael, Philanthrocapitalism. How Giving Can Save the World, New York, Bloomsbury Press, 2009.

Clinton William J., Giving: How Each of Us Can Change the World, New York, Knopf, 2007.

Fahrenthold David A., Hamburger Tom, Helderman Rosalind S., « The Inside Story of How the Clintons Built a $2 Billion Global Empire », The Washington Post, 2 juin 2015.

Paule Clément, « La santé publique à l’heure du capitalisme philanthropique. Le financement dans les PVD par la Fondation Gates », Passage au crible (14), 11 fév. 2010, disponible sur : http://urlz.fr/4roD

Sack Kevin, Fink Sheri, « Rwanda Aid Shows Reach and Limits of Clinton Foundation », The New York Times, 18 oct. 2015.

Schweizer Peter, Clinton Cash: the Untold Story of How and Why Foreign Governments and Businesses Helped Make Bill and Hillary Rich, New York, Harper Collins Publishers, 2015.

Feb 17, 2017 | Climate change, Development, environment, Passage au crible (English), Publications (English)

By Philippe Hugon

Translation: Lea Sharkey

Passage au crible n°148

Source: Flickr

The COP22 was held in Marrakech from 7-18 November 2016. Its aim is to implement the principles established during COP21 into practical steps. This summit is happening against a backdrop where most of the climate change skeptics have disappeared from the scientific field. However, some of their principles are advocated in some industrial countries by populist movements and political leaders hoping to win votes (Sarkozy in France, Trump in the United States). As for previous conferences, COP22 is faced with the issue of the climate debt and how to spread its funding.

> Historical background

> Theoretical framework

> Analysis

> References

Historical background

The United Nations Framework Conventions on Climate Change has been signed in 1992 and enforced in 1994 by the Conference of the Parties (COP).

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol constituted then a major step forward. Enforced in 2005 and ratified by 175 countries, it set the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ and introduced emissions rights, though exempting emerging countries from reducing their GHG emissions (Greenhouse Gas). However, the treaty did not take into account ‘virtual emissions’ or carbon leaks resulting from international trade. Moreover, the United States did not ratify it and the CDM (Clean Development Mechanism) had a very limited impact for Africa. Eventually, the 2009 Copenhagen Negotiations stalled.

On the contrary, the UN Agreement on climate signed in December 15 during the COP21 was a tangible achievement. Its aim is to limit global warming to no more than 2°C by 2050, and reduce CO2 emissions by 50% in 2010 and 100% by 2100. The text planned for a minimum funding of 100 billion dollars per year for the Group of 77 (G77). Unanimously approved by the 196 delegations, it is a diplomatic success nonetheless obtained through major concessions and uncontrolled promises. If it does rely on fair foundations, commitments and practical steps remain extensively blurry. Moreover, the negotiation on transparency failed. The document has nevertheless been ratified by major GHG emitters and enough States Parties to come into force.

If the COP22 could not benefit from the same global outreach as COP21, it nonetheless took place in Morocco as a symbolic recognition of the country’s pioneering energy transition. In Morocco, 97% of electricity is imported whereas energy consumption increases by 7% each year. The aim is to raise electricity supplied from renewables to 52% and reduce GHG emissions by 32% before 2030. Moreover, 64% of the climate expenses are allocated to adaptation and energy transition towards renewables (solar and wind energy), amounting to 9% of total investment expenditures.

Within the United Nations, Millenium Development Goals have been converted to Sustainable Development Goals, and this embodies a paradigm shift impacting both the Global North and South.

Theoretical framework

Climate Conferences can be understood through two major strands.

1. Strategies to cope with climate risks. Should climate hazards be tackled through proactive strategies or precautionary approaches? Should we favour compensation mechanisms or adaptation, resilience (capacity to recover from shocks) and mitigation (reducing the effect of damage)? Should environmental management be a question for local authorities or should it involve all parties on a global scene?

2. The lack of supranational authority on climate matters. Being formed by an assembly of sovereign States, the classic multilateral framework does not appear to be able to deal with climate and environmental issues. There is no supranational authority or global environmental organisation entrusted with the management of global common goods.

Analysis

There is little skepticism within the scientific community about the scale of recent and future climate change. Global warming has already been estimated to 0,6°C. It has led to extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, and long term reduction of precipitations in arid areas. Known effects of these climate hazards are desertification, hydric stress, induced vulnerability for agriculture, small islands and coastal towns. Eventually, these events dramatically impact public health and migration flows on a global scale. GHG emissions have quadrupled between 1959 and 2014, while the world population jumped from 3 to 7.2 billion individuals. GHG emissions have grown from 3 to 5 tons per capita. The location of main emitters has also evolved. In 1990, developed countries accounted for 2 thirds of the emissions when today the Global South – mainly emerging countries – account for half of it. However, GHG per capita emissions in the Global North reach 10.8 tons for only 3.5 tons in the South. Sub-Saharan Africa however only emits 0.87 tons of CO2 per capita.

But these localised emission data must be corrected as:

– They do not include the depletion of forest resources (carbon sinks) and non renewable energy resources, which are mainly exported. For example, in Africa, the adjusted net savings (national savings – (CO2 emissions + depletion of energy, forest and mineral resources) was negative in 2007-2009. The DRC, Congo, Nigeria and Angola featured the lowest negative net savings.

– They do not include the impact of foreign trade and delocalisation of GHG emitters in a context of globalisation where transnational firms might bypass environmental norms and easily yield to environmental dumping. Moreover, GHG emissions per imports and exports have to be factored in to enable the calculation of the carbon footprint for each segment of the global value chains. But eventually, delocalisation and externalisation of climate pollution seriously weakens the virtuous declarations of the Global North.

As climate negotiations do not factor in the transnational dimension of firms, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change ends up widely disconnected from trading negotiations, especially within the WTO or multi-stakeholder agreements. Within a globalised world and a market economy, environmental protection should be closely associated to trade and investment. On the contrary, negotiations and international agreements favour national sovereignty instead of taking into account the connections between the multiple government levels, from global scale to nations, regions and local authorities.

Moreover, energy transitions differ according to the stages of development of various countries. African countries could facilitate a green growth development pathway through the diversity of their partners, technological revolutions reducing costs and the ability to bypass some stages, without handling costly infrastructures dependent on fossil fuels. Public actors but also non-State actors are required to enable these differentiated pathways, if only benefiting from ad hoc funding, not limited to cash transfers captured by rentier States. The COP22 should allow to consider every possible scenario.

References

Hugon Philippe, Afriques entre puissance et vulnérabilité, Paris, Armand Colin, 2016.

Nations Unies Commission économique pour l’Afrique, Vers une industrialisation verte en Afrique, New York, 2016.

Stern Nicholas, Why Are we waiting? The Logic Urgency and Process of Tackling Climate Change, Cambridge, (Mass.) MIT Press, 2015.

Source: Flickr – Xavier Badosa

Source: Flickr – Xavier Badosa